The Disqualification Arguments

Voting Rights Academy: What the Amicus Briefs Tell Us

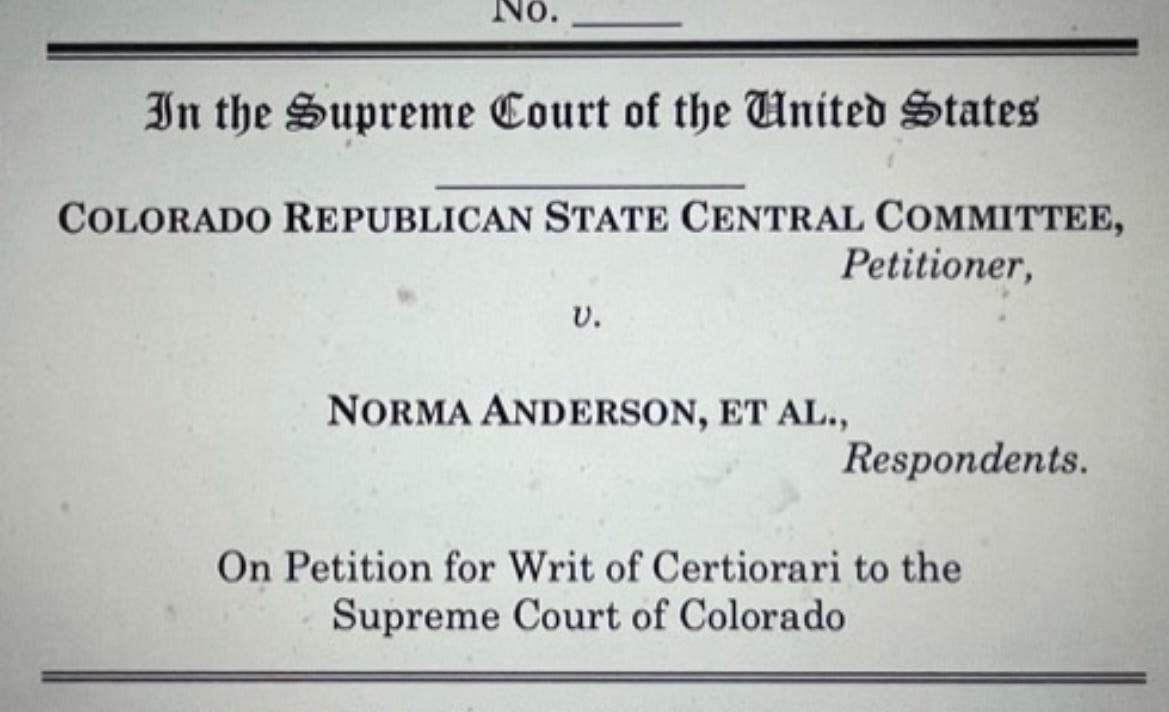

With oral arguments set for next week about whether Trump should be disqualified from the presidency, an avalanche of briefs has landed at the Supreme Court in recent days.

I decided to take a look at a few written by those who bring special authority or expertise to the debate—briefs I’m guessing the Justices and/or their clerks will review as they weigh the arguments.

Because the text itself is so clear, and because even Trump and his allies have spent little time rebutting the facts of his involvement in January 6, the running assumption is that the Court majority will be eagerly looking for some other exit ramp to avoid disqualification. Many of these paths center around who should make the decision about qualification—Courts or Congress?—and how they should make those decisions. Other pro-Trump arguments assert that the disqualification clause is somehow more limited in scope or application than the plain text appears to be.

The arguments in the Briefs I reviewed are clearly trying to cut off those exits. If the Court does not allow Trump’s disqualification, these are the arguments it will have to contend with.

Judge for yourself the strength of the arguments:

Brief 1: The Historians

Twenty-five historians filed a brief reviewing the history, intention and contemporary understanding/application of the disqualification clause—which appears as Section 3 of the XIV Amendment. Their brief sheds a lot of light on the arguments Trump and his allies are trying to make about why the disqualification should not apply to them. And they frame the argument in the way conservative justices say they approach things—textualism and originalism.

Those Who Wrote the Disqualification Intended it To Apply to Presidential Candidates

Trump and his allies argue that the disqualification does not apply to the president because the president is not an officer of the United States.

These historians point out that when the language was being finalized as part of the XIV Amendment, one opponent of the Amendment raised that exact objection—that the clause did not explicitly mention the President as being subject to disqualification for engaging in an insurrection. To which a supporter responded: ““Let me call the Senator’s attention to the words “or hold any office civil or military under the United States.” Senator Johnson then admitted his error, saying, ‘Perhaps I am wrong as to the exclusion of the presidency, no doubt I am, but I was misled by noticing the specific exclusion in the case of Senators and Representatives.’” No one disagreed with this interpretation.

The brief shepherds other evidence that the common understanding at the time was that the term “officer” of the United States included the President and Vice President. Numerous proclamations at the time referred to the President as the “Chief Executive Officer” of the United States. And this continued the understanding from the time of the original Constitution that the President was an officer of the United States, which came up under both the impeachment and emoluments clauses. One convention participant clarified: ““Who are the officers liable to impeachment? The President, the Vice President, and all civil officers of Government. In the election of the two first, the Senate have no control.’”

To make the point even more clear, the XIV Amendment authors were explicit that the clause would disqualify Jefferson Davis from running for president. And Davis himself acknowledged it.

The Disqualification Clause Was Not Limited to the Immediate Past (Ie. Intended for Only Ex-Confederates from the Civil War)

Trump allies argue that the disqualification clause was intended to deal with ex-Confederates at that moment in time. And was not to carry forward beyond those circumstances.

But if disqualifying former Confederates was their only goal, the historians argue, political leaders at the time didn’t need a Constitutional Amendment at all—the Congress had already passed several laws doing just that.

The Constitutional Amendment served a broader purpose, with an eye on the future: “Contrary to many laws that targeted former Confederates in southern states, Section 3 enshrined disqualification in the Constitution with generic language that does not reference the rebellion or former rebels. Unlike statutes, as part of the Constitution, Section 3 endures indefinitely, free of tampering by future Congresses”—as one Senator said, “to govern future insurrection as well as the present.” Efforts to limit the clause to a narrow time window were actually voted down.

“The framers crafted [the disqualification clause] to guard against the corruption of government by anyone involved in future insurrections who had taken an oath to support the U.S. Constitution.”

The Amendment Does Not Require Future Action by Congress To Take Effect

Responding to a common argument being made today, the historians argue that the disqualification clause does not require action by Congress to take effect. Instead, “it mirrored other constitutional disqualifications based on age, residence, and birth that did not require any action from Congress.”

Confederates, including Jefferson Davis itself, were instantly disqualified when the XIV Amendment passed—and said as much. The disqualification “executes itself… It needs no legislation on the part of Congress to give it effect….[It] commenced upon the date of the adoption of the fourteenth article.”

Brief 2: Judge Luttig

The second brief I’ll highlight was filed by arguably the most high-profile advocate of the disqualification clause (and my fellow Senior Fellow at Kettering), Judge J. Michael Luttig (along with some colleagues). Reminder: when I was a law student, Judge Luttig was one of the preeminent conservative federal appellate judges in America—snag a clerkship with him, and you likely would be clerking for the U.S. Supreme Court (and for Scalia, Rehnquist, O’Connor, Kennedy or Thomas) the following year.

Up front, Luttig takes on the arguments most likely to be the Court’s potential exit ramps:

Congress is NOT the Body To Resolve Disputes About Standards of Disqualification

Luttig argues that outside of several explicit exceptions, Congress is not the body to which the Constitution grants the power or duty to determine qualifications for office, including disqualification: “The founding generation would have considered it unthinkable to give Congress an unreviewable power, by a bare majority, to disqualify a President or a cabinet member when the facts or legal principles are in dispute.”

Instead, “it is an exercise of judicial power to decide disputed factual and legal questions about whether a particular person is qualified to hold office.” Specifically, “the Constitution confers the judicial power to adjudicate presidential qualifications first on the state officials and courts designated by state law, and ultimately on the Supreme Court.”

And, Luttig argues, the language of the disqualification clause is consistent with that frame/structure: “The last sentence of [the disqualification clause] reads: ‘But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.’ The words “[b]ut” and “remove” connote that the disability existed before Congress votes.”

(The historians make a similar argument: “Section 3 was very explicit about what Congress was required to do and not to do: Congress could lift any disqualification for office only by a two-thirds vote. Strikingly, however, the Section did not require any action by Congress to disqualify insurrectionists.”)

Luttig: “the words “remove such disability” in the Fourteenth Amendment confirm that the candidate is currently disqualified and will remain disqualified, unless and until there is an affirmative vote by two-thirds of Congress to “remove” that disqualification.”

Disqualification is NOT a “Political Question”

It’s a bedrock principle that the Supreme Court will NOT resolve disputes that it deems “political questions”—which is the reason it gave for not addressing partisan gerrymandering.

With many arguing that disqualification also raises an unreviewable political question, Judge Luttig addresses this argument head-on.

The first test for a political question is whether the Constitution grants a political branch the duty to determine the issue at hand (if so, the Court should not get involved). For disqualification, Congress was only given the power to remove a prior disqualification with a 2/3s vote—so the answer is no.

The other key test is whether there are clear judicially manageable standards a court can apply without crossing over into subjective political judgments. Luttig argues that crafting and applying legal standards related to the act of insurrection fall squarely within the judicial ambit: “Applying that term has a much firmer grounding in text and history than did applying “equal protection” to vote counting in Bush v. Gore”.

Touche :)

Along the way, Luttig also makes arguments that respond to common criticisms of the disqualification argument.

The Process Is Fair, and Abides by Due Process

The disqualification argument has been criticized for lacking due process, but Luttig turns this argument on its head—comparing a court-driven process versus handing the decision over to Congress instead:

“[T]he court process that the Constitution requires for adjudication of a presidential qualification dispute provides the safeguards and checks of the rule of law, federalism, and separation of powers. This includes evidence, procedural due process, recusals of adjudicators for bias, a ban on ex parte contacts, lower court review, the final judicial decision by the Supreme Court, and potential removal of a disqualification by a two-thirds vote of Congress.”

This is far better, he argues, than the argument that Congress should manage the process, as Trump advocates argue: “if Congress has unreviewable power over Section 3 disqualifications, as some advocate…that would lack all the safeguards and checks of the rule of law,federalism, and separation of powers. Congress consists of partisan politicians. There would be no requirements for evidence, procedural due process, recusals for bias, or bans on ex parte contacts. Nor any role for the states or another branch of the federal government.

As bad, any exclusive, unreviewable power of Congress to adjudicate non-member disqualifications would go both ways. A bare majority in both houses of Congress could ignore even the clearest of presidential disqualifications—a third presidential term—without any possibility of review by the courts.”…

“Nothing could be more contrary to federalism and separation of powers than giving a bare majority in Congress such partisan power with no possibility of veto or review by this Court.”

Apply the Clear Text Regardless of the Politics

Luttig argues that the clear text of the disqualification clause should be applied regardless of the politics of the moment—even it that means disqualifying a popular politician.

In fact, he writes, the clause provides a pivotal stopgap measure protecting democracy because it’s only relevant when an insurrectionist has curried enough favor to run and potentially gain office again.

In other words, the fact that Donald Trump remains popular with so many is not a reason not to apply it. The disqualification clause “has life only because it applies fully to those who violate its terms and still retain or regain enough popularity potentially to be elected or be appointed by elected officials. Section 3 would be a dead letter if the Court refused to apply it because an insurrectionist had popularity with large numbers of voters.”

Luttig also argues that disqualification should apply even if the insurrection in question is not national in scope: “the Civil War generation recognized that what started as an insurrection in a single state—the secession of South Carolina in December 1860—had metastasized into a Civil War…. Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment was the Civil War generation’s powerful deterrent to ensure that even an at-first localizedinsurrection would never again happen…That deterrent worked for over 150 years. The task of interpreting that deterrent commands respect.”

Finally, many rules in American politics disqualify individuals from office, or outlaw certain policies, that may enjoy popular support: “Not much would remain of our Constitution if this Court narrowly enforced the Constitution’s provisions when they potentially frustrate large numbers of voters. The Electoral College, separation of powers, bicameralism, six-year rotating terms for Senators, judicial review, the First Amendment, the Second Amendment, and the many Amendments protecting criminal defendants—and much more—often lead to binding results that are contrary to the majority preferences of voters in many states and nationwide.”

January 6 Was the Epitome of an Insurrection…

Luttig powerfully rebuts the argument that January 6 did not amount to an insurrection. He focuses not only on the physical actions of the day, but the broader aim of it all:

“The peaceful transfer of executive power is not merely a norm or tradition. It is the foundational mandate of Article II of the Constitution..…January 6, 2021 saw an insurrection against the Constitution because there was a threatened and actual use of armed force to thwart the counting of electoral votes that is mandated by the Twelfth Amendment, as part of the transfer of executive power that is required by the Executive Vesting Clause and the Twelfth and Twentieth Amendments.”

The “ultimate aim” of January 6 “was to extend Mr. Trump’s time as President beyond the four-year termination required by those constitutional provisions.”

At the same time, “the January 6, 2021 insurrection sought to prevent the vesting of the authority and functions of the Presidency in the newly-elected President. The Civil War generation certainly understood that the threat and use of force to prevent a newly-elected President from exercising executive power is an insurrection. Indeed, the activities of federal officials to prevent Lincoln’s inauguration were one basis for Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Indeed, Luttig highlights the parallels between 2020 and 1860: “As on January 6, 2021, the December 20, 1860 insurrection in South Carolina was against the forthcoming transfer of executive power to a newly-elected President….Mr. Trump tried to prevent the newly-elected President Biden from governing anywhere in the United States….The threat or use of armed force to prevent a newly-elected President from exercising executive power, whether on December 20, 1860 or January 6, 2021, is an insurrection against the Constitution.”

…And Trump Engaged in That Insurrection, With Clear Intent

Trump’s words, tweets and actions behind the scenes—both at the time and later—made his aim on January 6 clear: “Mr. Trump deliberately tried to break the Constitution—to incite threatened and actual armed force to prevent the peaceful transfer of executive power mandated by the Executive Vesting Clause and the Twelfth and Twentieth Amendments. That constituted engaging in an insurrection against the Constitution.”

Brief 3: The Brothers Amar

I always like to see what my former professor Akhil Amar writes on matters such as these—and I have no doubt the Justices and clerks will take a look at his Amicus Brief as well. His devastating brief in Moore v. Harper was one of the reasons I was convinced that North Carolina would lose that case.

Well, Professor Amar and his brother Vikram—ever the historians (and skilled writers)— did not let me down.

They assert that most of the arguments made against disqualification are quite easy to reject:

“Of course the president is an “officer” covered by Section Three. Of course a detailed congressional statute is not necessary to implement Section Three. Of course an ineligible person is ineligible unless and until amnestied. Of course a person can engage in an insurrection with words as well as deeds. Of course an insurrection can begin locally.”

You can read all these arguments in the lower half of their brief HERE.

But where they go in a unique direction is digging deeply into a moment of history they assert is the perfect parallel to January 6, and that informs how the Court should rule in the present day.

How’s this for an opening?

“Underlying Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, there resides a…key episode, an episode known to virtually all Americans in the 1860s and, alas, forgotten by most Americans today, even the learned. The episode has gone almost unmentioned in all previous scholarship on Section Three and in all previous briefing in this case. We believe that this episode is a key that can unlock many of the issues presented by today’s case.”

They go on to tell a fascinating story—about a man named John Floyd, who tried to use his federal position to pull off the “First Insurrection” (after Lincoln was elected and before onset of the Civil War itself we all know so much about). “The parallels between this insurrection in late December 1860 and January 1861 and the more recent Trump-fueled insurrection of late December 2020 and January 2021 are deeply and decisively relevant to today’s case….

“[I]f one understands— as did all the men who drafted and ratified Section Three—that before the giant insurrection that began in mid-April 1861 there was a smaller one that was also of central concern, then the matter looks entirely different.”

You again can read all the details here, but Amar’s point is that because Floyd’s actions also helped motivate the disqualification clause, they are relevant to consider now—and with that case as a backdrop, “the events of 2020–21 fall squarely within the heartland of Section Three.”

In fact, January 6 went further than Floyd:

“The Capitol did not fall in 1861. The First Insurrection of the 1860s largely failed in DC. But in 2021 the Capitol did in fact briefly fall, in an insurrectionist effort to impede the lawful counting of presidential ballots and the inauguration of President Biden. On January 6, 2021, the Confederate flag made its way into America’s citadel, as it had not on February 13, 1861—all because of what Donald Trump did do and did not do, over the course of many weeks, as recounted by the trial court in this case.”

The Floyd affair teaches another lesson:

“Section Three does not require that an oath-breaker actually use his powers of office in connection with his insurrectionary acts. But Floyd had done just that….Floyd did in fact bend his office to betray his oath….And so did Donald Trump, according to the facts as found by the court below in this case. Trump’s case is thus the easy case—a paradigmatic case—for application of Section Three.”

Another parallel: “Floyd’s misconduct also reminds us that engaging in insurrection, and giving aid or comfort to insurrection and insurrectionists, often involves a complex combination of devious actions and inactions. Certain inactions loom especially large when a current officer, with special obligations to affirmatively thwart other insurrectionists—indeed, other insurrectionists who have been egged on by that very officer—instead sits on his hands, smiling, as chaos erupts around him. This is precisely the case of Donald Trump.”

What Do You Think?

So those are some of the arguments from some of the best and brightest legal minds in America in favor of disqualification. Again, if the Court is to save Trump from disqualification, they will have to rebut all of these arguments.

What do you think? Please answer the few questions that follow:

Also in the history are the confederates who were elected but not seated by Congress. I hope that when the Dems take back the House in 2024, they will refuse to seat MTG, Scott Perry, Boebert, Jordan & the rest of the insurrectionists.

Thank you for this invaluable lucid summary of key amicus briefs in the CO disqualification case! I will share this compilation with students.