I was asked by Lisa Senecal, in a Resolute Square podcast the other day, if there was a key step we could all begin taking immediately to turn things around in our broken democracy.

And of all the things I could name, (you can see my answer at in the video below, at 18:45) I said…

…Precinct. Organizing.

As I explained: “we have to break down and organize at the ground floor…[W]e should be figuring out in every single county precinct, is someone doing the work or not…[W]e need to start taking ownership at the community level….The organizing work that has to be done, this is when we do it. If we start doing it in the middle of ‘26, we’re too late.”

To explain more why this is so important, let me share an excerpt from my book “Saving Democracy.” In this age of disinformation and lower turnout in areas where we can not afford it, what I wrote there is more important now than ever:

There’s one aspect of political party work that may be the most overlooked in all of politics. Which means there’s a single shift that could bring life to every community in every state in the nation. And that shift isn’t reliant on national forces and big dollars and grand, top-level plans to happen. In fact, back to the theme of this book, this is a shift you can help make happen.

They go by different titles.

In Cincinnati, we call them “precinct executives.” Elsewhere, they are called “committeemen” or “committeewomen.” In other places, “ward chairs.” Whatever they’re called, they are the basic unit of each city or county party structure in the country.

These are elected positions—or appointed by a county party if there is a vacancy. As members of the executive committee of the city or county party, these posts play a formal role in the operation of the party, in its endorsement process, and in the selection of its leadership. Often, that governing role is what drives folks to run for these roles, or why they’re recruited to do so.

But here’s the thing. . . each precinct executive (to use the term where I live) also, formally, represents a specific voting district of their community. That precinct or ward—a handful of specific, contiguous blocks of a community—comprises the most basic building block of the entire nation’s political geography. Fortunately, these precincts usually include hundreds of voters—a manageable number. In cities, highly concentrated— which means walkable. In rural areas, more spread out—but still drivable. All callable.

Manageable.

Small enough to put our arms around in a meaningful way.

Now, amid all text bank and digital messages and fancy TV ads aimed at voters, do you know what single change would forever lift turnout and alter outcomes in American elections more than any other? Everywhere?

Simple: if every Democratic precinct executive or committeeman or committeewoman in this country took ownership of the precinct she or he is elected to represent. If they all made the simple decision to engage (permanently) and organize the manageable number of residents living in those small geographic regions.

It’s that straightforward.

But, in my experience, almost none do this. Precinct executives dutifully go to meetings and pitch in in other ways, but only a tiny percentage actually work their precincts. Even worse, many precinct and ward positions sit vacant. Add it up, and the lack of engagement at the precinct level marks the single most wasted voter engagement opportunity in American politics.

Why don’t precinct executives take ownership of their precincts?

In many cases, it’s because no one ever asks them to. No one ever sets that basic expectation, or gives them a job description of what the role they ran for means, or could mean if they did it well. No one lays out even the most basic tasks that could make such a difference in the role they chose to occupy.

Tasks as simple as:

recruit a street captain for every street of your precinct, who then takes ownership of that street.

recruit an apartment building captain for every building of your precinct.

engage every public-serving business in your precinct, and get them in the game if they’re interested.

task every one of those captains to engage and get to know the voters on their street or in their building—long before actual elections—and whenever new folks move in.

bring residents together on a regular basis, both captains and anyone from the precinct who is interested; or send them regular emails

create a precinct Facebook page, or other way to communicate on a regular basis;

do a sweep of the community months before each election to ensure folks are registered.

do the same for early voter opportunities.

do the same for election day voting.

Or go even bigger: create a standing precinct organization—ten, thirty, fifty members—that comes together regularly, then uses the footprints of all its members as the basis of broader work. With that group, build a long-term plan for the precinct.

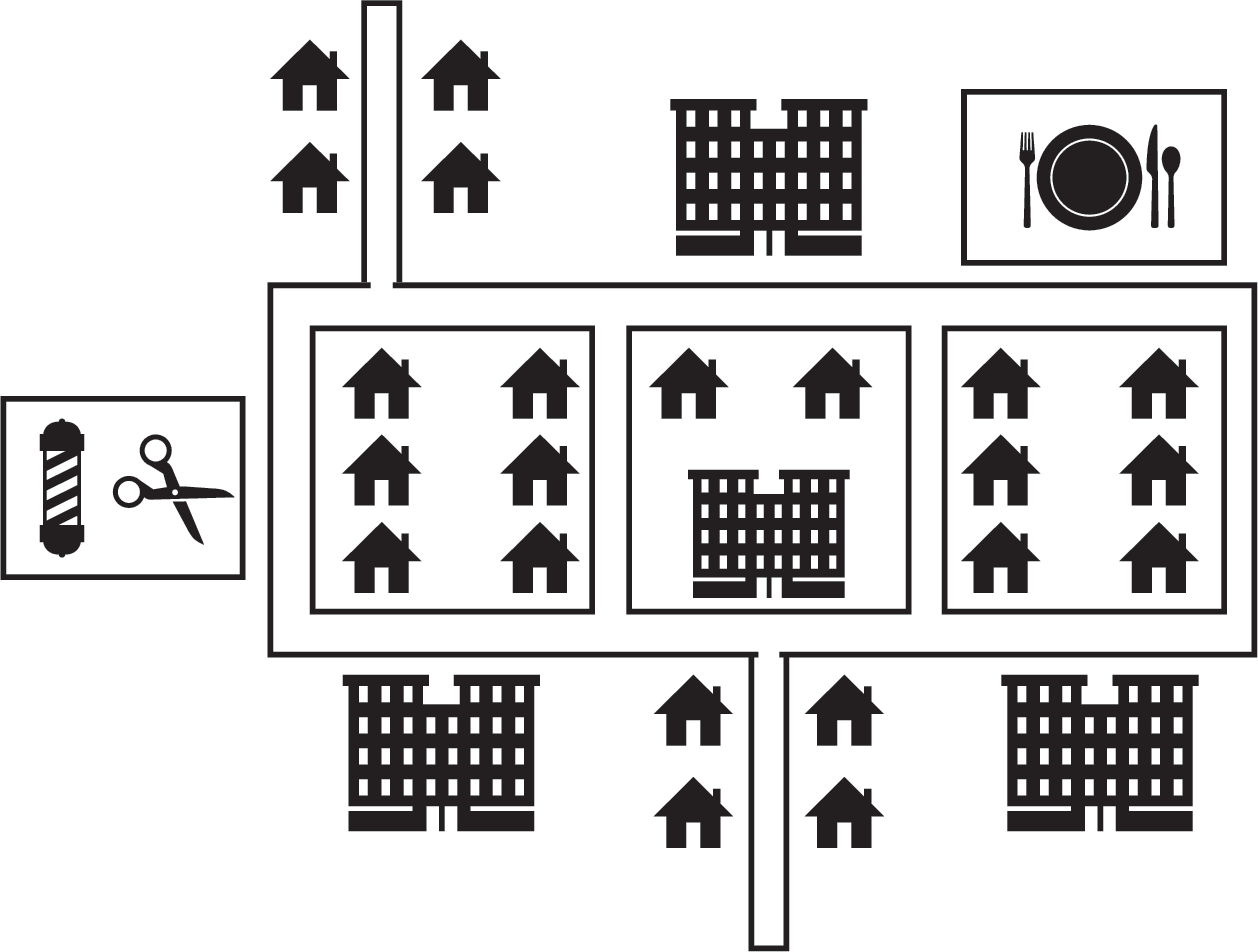

One of the greatest benefits of robust precinct organizing is that it, like community-based organizations, fills gaps otherwise left by political operations.

First, it engages people far earlier than last-minute knocks on doors; those late knocks are no longer stand-alone transactional moments, but the last of a steady series of engagements.

Second, the conversations are more authentic, with a neighbor—not a stranger. This can cut through disinformation and social media nonsense more than anything else.

And third, the precinct strategy can target all voters, with extra focus on disengaged and suppressed voters, as opposed to the far narrower approach of most campaigns.

Doesn’t this all sound pretty straightforward? Common sense? What a political outsider would assume is already happening?

In my experience, almost none of this happens anywhere!

Which is why I say, again—if every single Democratic precinct executive took ownership of her precinct, doing this work, participation would rise, disinformation would be diluted, and outcomes would change. Heck, if 50 percent of Democratic precinct executives did so, outcomes would change. Thirty percent, still a big change.

What does it take to make this happen?

It takes people deciding to do it—deciding that our democracy matters enough to make these critical roles about engaging the community, and not just going to insider meetings. And it takes leaders asking them to do it—setting that new expectation that if you are a president captain, you own your precinct.

Once party organizations and individuals have decided to take that ownership, then do the following:

write up a basic job description for the precinct executive role;

share it with every new precinct executive as soon as they’re elected—set the expectation from the outset;

organize early training for precinct executives on how to do the described job;

have the broader city or county organization establish goals and deadlines for what each precinct should achieve by when;

do the work;

do it so broadly and actively that you build the social proof that this is what you do if you are a precinct executive. This is the new expectation—the new normal; and

build a long-term plan.

So wherever you live, know that you’re sitting on the greatest untapped opportunity to change outcomes in American politics:

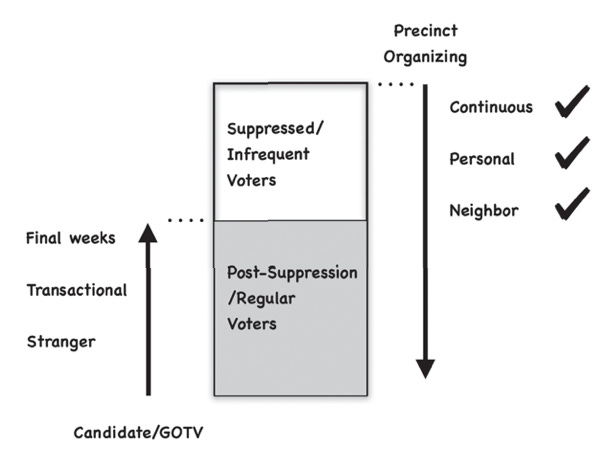

If you’re a precinct captain, own your precinct. That is one hell of a footprint.

If you’re not involved in the party, but you’re a registered Democrat and you’re sitting in a precinct that’s vacant, run for it next time and do this work. See if you can get appointed to it in the meantime.

Whether you’re involved in the party or not, if the precinct you live in is not being organized by anyone, figure out who the precinct executive is, track them down, see what they’re doing, and offer to do the organizing work that needs to be done. Of course, build a long-game plan for the precinct.

Whatever you do, start the conversation and work to make this happen. Wake up this dormant infrastructure.

Can this really work, you may be asking?

Yes it (we) can! It’s exactly what the early Obama campaign did when people organized house parties in communities across the country; they didn’t see active precinct organizing where they were, so they did it themselves. That model drove one of the most historic campaigns our nation has ever seen.

This is the lowest hanging fruit out there to save democracy. Let’s care enough to grab it.

Day 20 — December 20, 2024

The House reached a bipartisan budget agreement to keep funding the government and avoid the looming shutdown. When Speaker Johnson spoke to the media after the passage of the deal, he made it clear that he had talked to Elon Musk about it 15 minutes before talking to Trump.

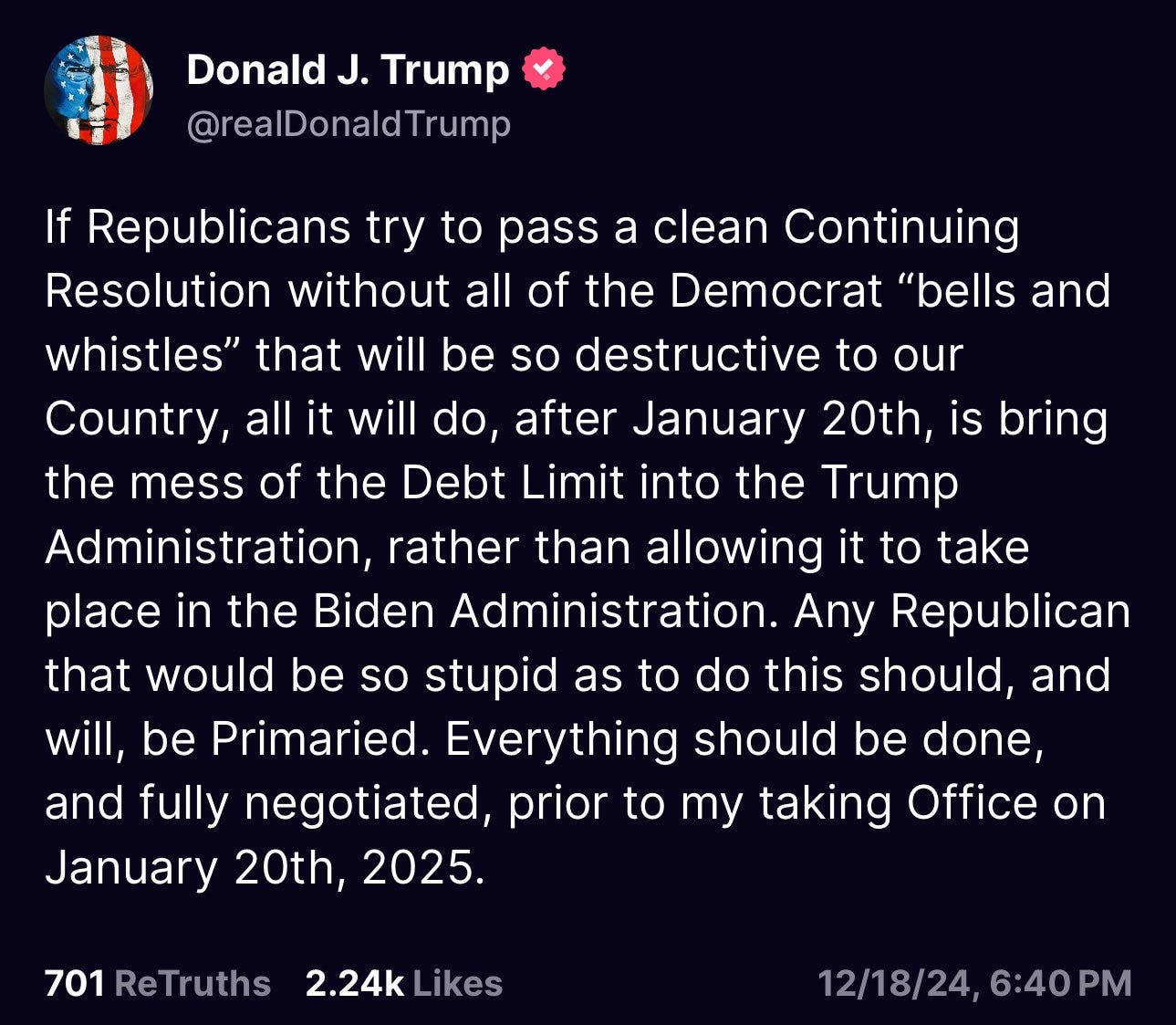

Trump had threatened to primary any Republican who voted for a “deal” that did not include a debt ceiling extension, this deal did not have an extension. Yet 170 Republicans voted for it.

Following up on yesterday’s newsletter, I did a quick video describing what the Musk-induced chaos foretold. Here it is:

Great ideas. Westerville has Westerville Progressive Alliance. They do a fantastic job.

Thank you. Just reached out to my county Dems and asked how to get involved in their precinct program. I didn't know there was such a thing.