This past August, the measure called Issue 1 in Ohio—the Ohio GOP’s effort to raise the threshold (to 60%) for voters to amend the Constitution—was soundly defeated.

The highly effective campaign that sent Issue 1 down in flames had a simple name: the “One Person, One Vote” campaign.

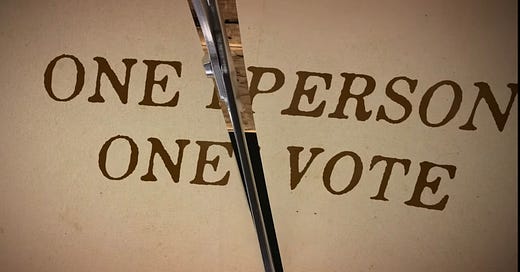

And, no surprise, the dominant theme of the campaign was that by requiring a supermajority to amend Ohio’s Constitution (41% defeats 59%), Issue 1 would’ve upended the “sacred principle” of “One Person, One Vote.” Here’s an image from one of the campaign ads aired endlessly over the final weeks of the campaign:

Now, Issue 1 lost for a host of reasons (thank you to all who helped!), but trumpeting that principle (so powerful that the campaign named itself after it) clearly made a difference.

But it begs the question—how “sacred” has the “one person, one vote” principle been in our democracy? And for how long?

Does it go back to the Founding? The 14th or 15th Amendments? The Voting Rights Act?

Take the poll, then scroll down…

.

.

.

.

.

The answer may surprise you.

What is now a bedrock principle of American democracy actually emerged through the civil rights movement, and a Warren Court dedicated to eradicating voting systems that were anything but one person, one vote—yet still entirely accepted at the time.

In some cases, they were—no joke—one person, one hundred votes.

Class 15 of my Voting Rights Academy explores the historic case that sparked that revolutionary change. A case that took a slogan handwritten on signs amid civil rights protests, brought it to the highest court in the land, and locked it into American law and culture so effectively that it still resonates in campaigns 60 years later.

Georgia, 1960: One Person, One (Hundred) Votes

In 1960, when Fulton County resident James Sanders voted in the primary election for Georgia’s statewide offices, he got to cast one ballot. Only one vote for each election on the ballot.

Technically speaking, so did everyone else in Georgia who voted in the same election. One ballot—one vote for each election on that ballot.

But as James Sanders did the math, he calculated that his one vote was not counted equally vis-a-vis many other Georgia votes. In fact, he believed his vote counted as little as 1/100th of votes cast by some Georgia residents.

How did he reach this number? It was the process Georgia used to count those votes.

Let me explain:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pepperspectives to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.