Hypothetical: imagine if right after last year’s train derailment in East Palestine, an Ohio agency found that the chemicals leaking from those railcars posed an imminent danger to people in the area, and then ordered that the railcar leak be plugged immediately.

Then imagine that another Ohio governmental body (controlled by railroad interests) overturned that decision, allowing the leak to begin again and continue unabated for another six months. Just on and on, for half a year.

Preposterous, right? Outrageous.

Well, thanks to some good reporting by Cleveland.com, we now know that what I just described actually happened in Athens County, Ohio (where I spoke last night) over the past six months. The leak was not from a derailment, but from injection wells—sites where a toxic cocktail of water and other chemicals (the makeup of which the industry insists is a “trade secret”) from the fracking process are transported to the site and injected below ground.

And while the source of the danger was different than my rail example, the response played out just like my horrible hypothetical:

The controversy had been years in the making. And in June of last year, the state agency (the Ohio Department of Natural Resources—ODNR) shut down injection wells in Athens County after concluding that toxic waste (“brine”) injected into the wells was leaking beyond the wells, and rising to the surface in the surrounding area (largely detected because it was emerging in other “production” wells). The ODNR warned that the leakage posed an “imminent danger to the health and safety of the public and is likely to result in immediate substantial damage to the natural resources of the state.” Despite that dire warning, in October, a state body overturned the decision and allowed the leaking of the toxic brew of chemicals to begin anew. And for six more months, it continued! Until last Friday.

Apparently if you can’t see the danger, and if the media isn’t covering it, the State takes its sweet time protecting the health and safety of everyday Ohioans and communities.

But something else happened along the way. And it involved the institution of Ohio government that let it happen.

Notice that in my hypothetical above, I included the detail that a body dominated by railroads was the one that allowed the danger to continue.

Would such a thing also really happen?

Well, in this Athens case, it’s exactly what happened.

And it is one more glaring example of how broken Ohio government is.

In fact, worse than broken.

It’s a stacked deck—stacked in favor of those who make big bucks in and from Ohio, and stacked against those who too often pay the price—everyday Ohioans and communities, and their healthy and safety.

So stacked, in fact, that not a single voice around the table that re-initiated that leak was there to speak up for the public interest. (Even though, by law, someone is supposed to be!)

Read on to see how it all happened, and who made it happen…

A Stacked Oil and Gas Commission

Just as I was writing Monday’s post about how control of less high-profile public institutions allows those in power in Ohio to maintain power, satisfy special interests, and accomplish key components of their agenda, the story broke about Athens County.

So I decided to take a look at the body of Ohio government that allowed it to happen.

It’s called the Ohio Oil and Gas Commission.

Its website describes its role as follows: “The Commission receives and hears appeals of any person claiming to be aggrieved or adversely affected by an order by the Chief of the Division of Oil & Gas Resources Management.”

OK. The website calls it an “advisory council,” but it operates like a court. An appeals court.

So who sits on this important court-like body, with the power to allow actions to protect the public health and safety to either move forward or be stopped in their tracks?

And in this case, why in the world would the body allows months to pass while an expert said toxic waste was creating an imminent danger?

The answer will floor you (unless of course you’ve been reading that Governor Mike DeWine allowed First Energy to hand-pick the chairman of the commission that regulates First Energy).

By Ohio statute, there are five different members of the commission, and each is appointed by the Governor for a five-year term. But the Governor can’t just appoint anybody to the five seats. By law, as its website explains, each member is supposed to bring a specific interest or expertise or perspective to the table:

a member who represents “independent petroleum”

a member who represents “major petroleum”

a member “learned in geology” or “engineering”

a member “learned in oil and gas law”

a member “representing the public”

So on the surface, it looks like when Ohio lawmakers created this body, they were seeking to balance a number of perspectives and skill sets. And that makes sense, since this is a deliberative body tasked with making decisions that will need to balance a variety of interests.

Let’s break down the attempted balance:

The petroleum industry is represented by the first two members. They obviously will bring an industry viewpoint to the table, but they are only two of the five members, and presumably balance the different perspectives of “independent” and “major” interests.

Two other members bring legal and scientific expertise (geology or engineering) to the table. This too would seem to add some balance and expertise—differing perspectives—to the group’s deliberations, beyond pure industry interests. A legal mind. A scientific mind. Makes sense.

And a fifth member represents the public, which of course brings a critical and distinct interest (public health, safety, in addition to economic, etc) from the other four members. (I’d argue that the “public” should have more representation than just this one member—but at least they have one member in this set-up.)

Ok, so that’s the theory. A balance. Differing perspectives.

What's the reality?

Who were the actual people Governor DeWine appointed in these seats so that last October, this group of five unanimously allowed the suspect wells to restart operations—and their toxic, dangerous leaks?

Well, let’s walk through the five who made the decision. Here they are, on the order:

Two members of the commission are what you’d expect—representatives of two companies in the petroleum industry:

One member is Christine Shepard-Desai, who represents “independent petroleum”; she serves as the Vice President and General Counsel for Pin Oak Energy Partners, which describes itself as “focused on the acquisition, exploration, development and production of crude oil and natural gas assets.”

The other member representing industry, this being the seat representing “major” petroleum, was Brian Chavez. As his bio page describes, Brian is “the manager and owner of Reno Oil & Gas, LLC, which manages the operations and field maintenance of more than 400 conventional gas and oil wells. He is also the owner of Chavez Well Service, LLC.” (Brian left the commission recently to become.…an Ohio State representative).

OK, those two meet the criteria. The industry has its representation.

But what about the other three? How did DeWine balance other perspectives and expertise that the statute clearly intends?

Well, above you will see the signature of Frank Reed. At the time, Reed was the member of the commission in the “learned in geology” slot.

But when you look at his background, that seems like an odd fit.

The Ohio Revised Code makes clear that this person “shall be a person who, by reason of the person's previous training and experience, can be classed as one learned and experienced in geology or petroleum engineering.” Again, such scientific expertise would presumably bring an important perspective to a conversation about toxic leaks.

But Frank Reed is neither a geologist nor an engineer. Nor has he been trained as one. He’s an attorney, with an undergraduate degree in liberal arts. Now as a lawyer and liberal arts major myself, I have nothing against those educational paths. But those degrees and career paths would not appear to satisfy the clear intent of the statute, which is that the person be “learned and experienced in geology or petroleum engineering.”

And then let’s examine what kind of lawyer Frank Reed is. He clearly has a long and distinguished career in the law—both within government originally and then as a private lawyer. He works for one of Ohio’s most respected law firms. But it’s pretty clear from his resume that his private practice for many years has been as a lawyer for the industry. As his bio says: “Mr. Reed advises clients on issues of environmental compliance; defends companies against environmental enforcement activities initiated by Ohio or U.S. EPA. His clients have industry experience in the area of manufacturing, chemicals, real estate development, hazardous mate0rials, construction, foundries, solid waste disposal, scrap tires, construction and demolition and debris disposal, septic tanks, and used oil recycling.”

Another part of his bio says: “He has experience in defending general litigation including class actions lawsuits, home rule, Eminent Domain, zoning, environmental, as well as transportation issues with a concentration on matters involving air, water, solid waste, hazardous waste and underground storage tanks.”

All that speaks for itself. And makes clear that the Commission’s “geologist/engineer” is actually a lawyer whose day job (for years) is to represent the industry when its members need defending, including from environmental problems they create.

So that’s our “learned geologist” member. (By the way, Frank has recently been redesignated as the “learned lawyer” of the group).

OK, now let’s move to commissioner number four—the one who’s supposed to be “learned in oil and gas law.” His name was Andrew Thomas. (His term has since expired). And like Reed the non-geologist, Mr. Thomas also has a lengthy legal resume.

But again, a close look at his practice shows that he too represents the oil and gas industry. He served as Of Counsel at Meyers Roman, another respected firm. And Meyers Roman touts its energy group, where Thomas serves, as follows: “The Utica/Marcellus shale basin has led to the rapid growth of an oil and gas industry in Ohio. Our Energy Law Group has extensive experience in nearly all areas of oil and gas law, with specific expertise in representing service companies. In addition, we also have experience in representing landowners, drilling companies, lenders, and operating companies.”

Ok — so now that’s four out of five members of this court-like body who either work directly for the industry or represent it as attorneys.

That leaves one last member.

The “Public” Representative?

Remember, this is the member that the Ohio Revised Code spells out “shall be a person who, by reason of the person's previous vocation, employment, or affiliations, can be classed as a representative of the public.” ORC 1509.35.

What a relief!

At least one person to balance out the four commissioners who it turns out make a living leading or representing the oil and gas industry. Even though outnumbered, perhaps this “public” representative has deep roots in the communities impacted by these decisions. Perhaps she or he is such a passionate advocate for the separate interests of the impacted public (health, safety, economic well-being, etc.) that there’s at least a robust voice on the commission for everyday Ohioans. A public conscience. One who can win over two of the others in a health emergency like the commission faced last Fall.

So who did the Governor select for this critical position? The person who’s supposed to speak for the public—the communities and people impacted—and potentially balance out the other voices on this commission?

Well, you’ll see above that his name is Philip Parker. He lives in the Dayton area.

Hmmm. Now I love Dayton, but as far as I know (and as I experienced in my two-and-a-half drive from Western to Eastern Ohio last night), it’s not all that close to the communities most directly impacted by oil and gas wells, and risks they present. So at least in terms of representing the “public,” that’s already a head scratcher.

But of course, geography isn’t a disqualifier. Maybe there’s something else about Mr. Parker’s background that suits him to stand up for the “public” of Ohio (and the part of Ohio most impacted) in these cases.

So what was Mr. Parker’s “previous vocation, employment, or affiliations” (as the statute spells out) that suited him to be a representative of the “public?”

A quick search shows that he served 27 years for the Dayton Area Chamber of Commerce, most recently as its president and CEO.

Now I’ve worked with a number of regional Chambers and respect much of what they do, but I know that, just as his own website describes, the Chamber is an association of businesses. As Parker himself describes it: “is a business-focused organization dedicated to regional economic development, business advocacy, and diversified member services.” And from his time in that role, he summarizes his personal experience as follows: "During his professional career, he has obtained an extensive background in working with trade associations and businesses of all sizes in the Miami Valley region as a champion for our free enterprise system.” Now retired from the Chamber, Parker remains a business consultant — as his website pitches: “You know your business will prosper when you are guided by a professional who can bring you success on your first day out."

(Another note on Parker: back when current Lieutenant Governor Jon Husted was a state Senator, Parker hired Husted to lead workforce development efforts at the Dayton Chamber.)

Again, a guy who’s spent his career working with and advocating for business and trade associations and their members—who is now is a consultant looking for business clients—doesn’t sound like the champion for “the public” we need in that fifth commissioner spot, especially now that we know that the “public” representative is already outnumbered by four folks who represent the industry. In fact, he seems like he might have a mindset quite similar to the other four commissioners I’ve already described.

To confirm my hunch, I reached out to some people from the Dayton area I trust and asked them what they thought of Mr. Parker serving as the “public” representative on Ohio’s Oil and Gas Commission. First, they had no idea. The second response when I explained it: “OMG.” The third, when I asked for more: “I am shocked that Phillip Parker is on the oil and gas commission as a representative of the ‘public.’ The only interests he has ever represented are his own and corporations.”

So, that’s our five.

And when that appeal from the shutdown order came before this body last fall, the agency that had declared imminent danger faced a commission made up of two representatives of the oil and gas industry, two lawyers for the oil and gas industry, and a man who spent his career serving and advocating businesses and trade associations.

Now that is a stacked deck.

And the commission re-opened the wells.

Making Things Worse

And what happened as a result of their decision?

Well, we now know from last Friday’s order—finally shutting down the wells—that the Commission’s actions literally re-started the problem.

Here’s the added, horrific details we learned:

Not only are the injection wells likely leaking the hazardous chemicals, but this leakage “pose[s] a real threat to the limited freshwater resources relied on by Athens County residents,” and an “increasing threat to drinking water wells.” The leaks mean that the “potential speed of transport of [the hazardous chemicals] to depths used for drinking water would be significantly shorter than would have been expected….[and that such] contamination may not be quickly discovered.”

But do you know what we also learned?

First, we learned that the company operating those wells already had an expert report “in its control for years” that found it was leaking beyond the wells, but had not previously disclosed that fact. It only turned those reports over as part of the discovery.

Second, we learned that the October decision by the Commission to re-open the wells re-initiated the toxic leaking!

And how do we know this?

One of the key pieces of original evidence that the suspect injection wells were leaking was that an expert detected “brine and pressure” at a nearby “production” well at an amount he had never seen in his decades of inspection. The presure, he concluded, “was not natural and could only be caused by over-pressurizing the formation,” but was likely coming from leakage from the suspected injection wells. The toxic brew was leaking from the site of the injection wells and rising to the surface elsewhere, including in other wells. (And who knows where else?!)

Well, wouldn’t you know it—when the agency first ordered those injection wells shut down last June, that unnaturally high level of pressure at the nearby wells fell to zero. The problem went away. Hmmm.

But then after the Commission allowed the injection wells to start operating again through its October 2023 order, the pressure in nearby wells spiked back up to its old, elevated and unprecedented level: “There is a documented correlation between the timing of the [injection wells’] operations, or lack of operations, and the pressures at these production wells.”

In layman’s terms—the leak of hazardous chemicals was indeed coming from the suspect wells, and when the commission turned the wells back on in October, they restarted the leak (which had been stopped) all over again!

Ohio government did this to its own people.

Shocking Yet Predictable

It’s all a stunning set of facts, isn’t it?

But when you think about it, completely predictable.

Take a step back. I harp on this all the time.

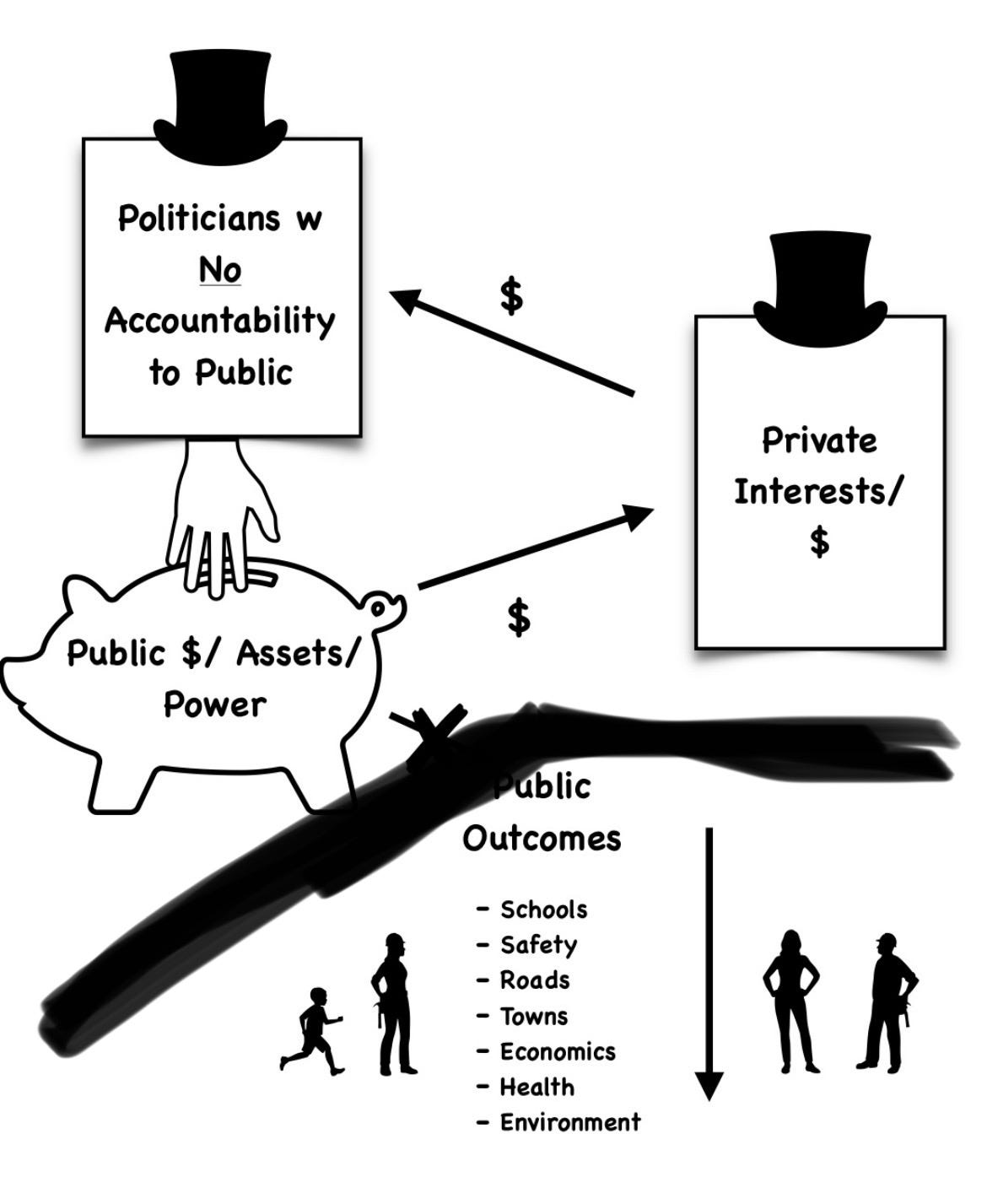

The MO of Ohio government today (and many red states) is that politicians take public assets and functions and power they control, and hand them over to private interests (who in turn support them, or supported them to give them that public power in the first place):

They did it with ECOT (the for-profit charter school scam). They are doing it with the universal voucher giveaway. They did it when they allowed First Energy to hand-pick the man who would regulate them (through the Public Utilities Commission).

And they did it here. A body stacked with those who represent business and the industry itself is the one determining if a dangerous situation should be resolved, or continue. And even when the law says there should be someone representing the “public” on that body to speak up for public health concerns, the public clearly isn’t at the table.

So as bad as it is, in all these situations, the result is entirely predictable. And always the same: The public pays the price for the harnessing of public functions and public power to serve private interests and private gain.

And that is the true corruption corroding Ohio.

It’s not the corruption that is usually talked about—things like personal bribes and payoffs.

It’s the far deeper and broader corruption of public service itself into a twisted version of private service, paid for buy the public, and the costs of which are shouldered by the public.

And that deeper corruption of public service itself is what’s doing the far greater damage over time in states like Ohio.

And until we demand that it change—through countless reforms and throwing out all those whose mindset it to corrupt public service for private ends—the results will always be the same.

Sounds a lot like Flint’s water situation. These scumbags don’t care whose lives they destroy.

Sad and outraged GET MONEY OUT