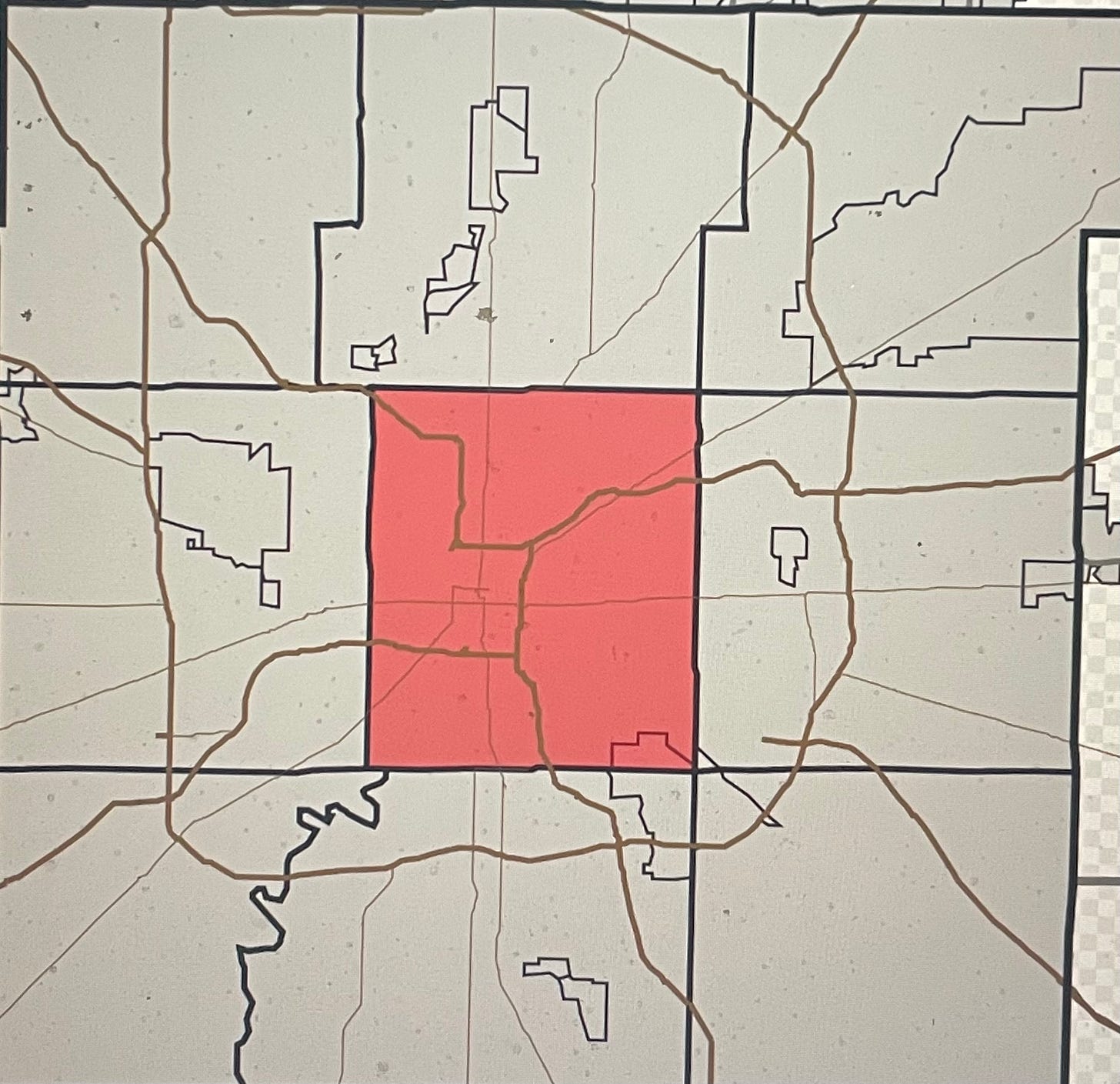

At the heart of Indianapolis—literally, the “center square” of nine squares that make up the larger “square” of Marion County—is a township aptly named Center Township.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Center Township comprised a highly segregated community— 97,000 Black residents, and 35,000 White residents. The community faced distinct challenges and had distinct needs: around housing, poverty, education, and crime.

The good news was that Center Township was large enough in population that it encompassed the size of two statehouse districts and a state senate district—so in theory, it should at least have had representation advocating to address those challenges.

But when the residents of Center Township looked around, despite their size, they rarely if ever had elected officials fighting for them and their interests in the state legislature. Again—even though they were a distinct community with enough residents to populate two entire statehouse districts.

Why were they left out?

A number of reasons contributed, no doubt. But some contended that a specific electoral device systematically deprived them of the representation they deserved. And two Black residents of Center Township, Andrew Ramsey and Mason Bryant, went to court to try to fix it.

Ramsey, Bryant and other plaintiffs argued that they were underepresented because Marion County elected its 15 representatives to the statehouse through one large “multi-member district” (all 15 were elected as a slate across the entire county/district) as opposed to 15 separate, single-member districts (which was how Indiana’s rural communities voted for their members). Because Center Township was large and discrete enough to have two of its own districts, the plaintiffs argued, the multi-member district arrangement deprived its residents of representation in a way that violated Equal Protection.

Ramsey, Bryant and others presented their case at the federal district court level—marshaling evidence that while they were not represented, the residents and interests of more affluent and White communities of Marion County were. That the multi-member district’s representatives over-represented those better-off and largely White areas.

Their evidence was so strong, it convinced the federal district court to rule in their favor.

But then the Supreme Court took the appeal. And that’s where Center Township lost.

The majority opinion summarized their claim as follows: “that any group with distinctive interests must be represented in legislative halls if it is numerous enough to command at least one seat and represents a majority living in an area sufficiently compact to constitute a single-member district.”

And that proposition, the Court concluded, simply did not hold legal water. If it did, the Court cautioned, “it would be difficult for a great many, if not most, multi-member districts to survive analysis.”

And that ended the case—a tough loss for Ramsey and Bryant, and the residents of Center District they were fighting for.

* * *

On reading this, though, many of you may be puzzled.

“Multi-member statehouse districts?” Those sound odd. What are they? Where do they exist now?

And your reaction is a hint at what happened after this challenge from Indiana was decided in 1971.

Because the argument Ramsey and Bryant raised on behalf of Center Township ultimately won the day. Their challenge cracked the door; and later cases and then Congress would fling that door wide open.

It turns out, Ramsey and Bryant were ahead of their time. Because the very principle that the Court scoffed at—that “any group with distinctive interests must be represented in legislative halls if it is numerous enough to command at least one seat and represents a majority living in an area sufficiently compact to constitute a single-member district”—largely became the law of the land over a decade later.

And in the precise way the Court predicted, once established, that principle would indeed eliminate almost all multi-member districts around the nation. And just as Ramsey and Bryant had asserted, the demise of “multi-member districts” like Marion County’s would unleash a dramatic change in the representation of urban communities across the country.

Oh, one more thing.

Ramsey and Bryant’s argument endures even to this day. High-profile decisions earlier this year, applying the same principle, are undoing recent discriminatory gerrymandering in a number of states. The results of these cases may change the makeup of the House in 2024.

It’s a fascinating story—yes, a hopeful story—so I’ll dedicate Class 19 of my Voting Rights Academy to telling it.

Primer: Multi-Member Districts

The residents of Center Township went to court at a time that Black voters were registering in far greater numbers around the country. So multi-member districts across the nation emerged as a key obstacle minimizing the power of this growing Black electorate.

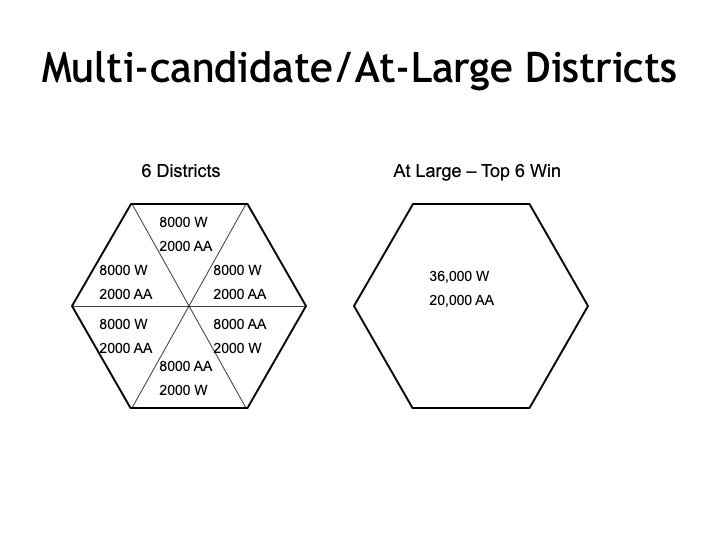

Here’s how it worked: as opposed to single member districts, used in rural areas and with smaller towns, these large multi-member districts were often used in determining representation for larger urban/diverse areas. A much larger area and population would be treated as a single district for an election, but would be represented by multiple legislators (eg. one district the size of, say, six single-member districts would elect six representatives).

At-large elections within these multi-member districts would determine which candidates went to the statehouse. And in the process, those elections would largely eliminate the more diverse representation that would have resulted if all the representatives from that urban area had instead come from single-member districts. The diagram below shows how:

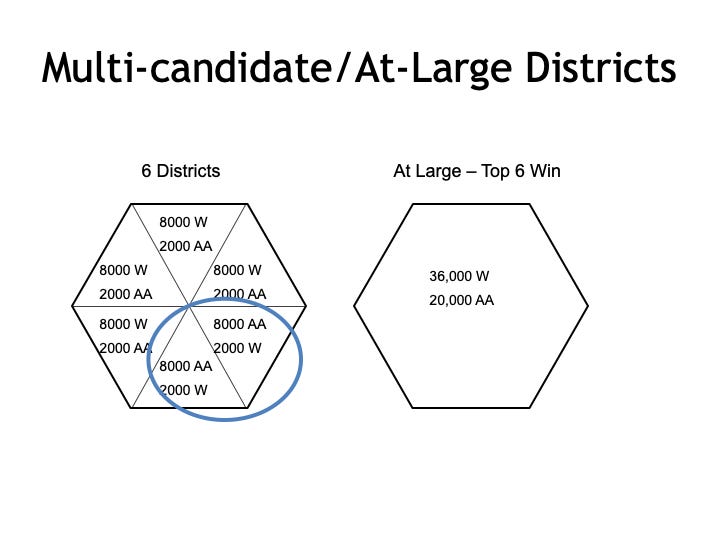

Think of the two hypothetical districts with the 8000AA/2000W populations as Center Township:

These communities would have their own representatives if within single districts, but that representation disappears once absorbed within a multi-member/at-large district.

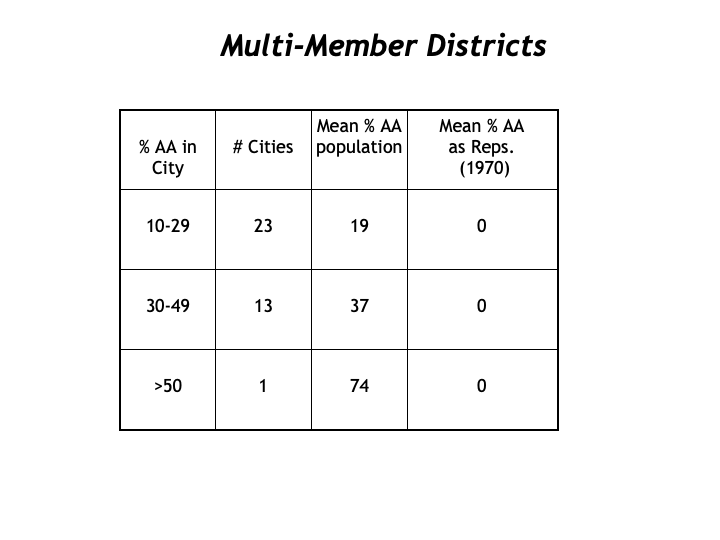

At the time of the Indiana litigation, this was not a small issue. Statehouse elections for dozens of major cities were held this way. And the impact of these districts was dramatic.

The chart below shows how brutally effective these multi-member districts were in locking this new black electorate out, even in districts with significant African American populations:

The Court Enters the Fray

The Indiana Case — Whitcomb v. Chavis (1971)

In 1971, in that Indiana case—called Whitcomb v. Chavis—the Court ruled against the effort to eliminate multi-member districts. But in rejecting the claim, the Court did leave some breadcrumbs of hope. A pathway out for future cases…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pepperspectives to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.