Next week, there will be a lot of attention on the Supreme Court case, Moore v. Harper. That’s the case where the Court will review the rogue “independent state legislature” theory (ISL) that state laws involving elections should not be subject to review by their own state courts. I’ll address that insane theory in a later newsletter.

But there’s another case with a huge impact on future American elections that’s ALREADY been argued, and it’s not getting nearly the attention it deserves. And while it remains unclear if the Supreme Court will buy the ISL theory, my guess (and fear) is that in this other case, the Court’s conservative bloc has already voted to gut the Voting Rights Act’s long-established protection against discriminatory gerrymandering.

Think of it as the next shoe to drop after Citizens United and Shelby County, and it couldn’t come at a worse time. Aggressive GOP gerrymandering in 2021 (which violated prior VRA precedent and state laws) was essentially the tie-breaker that secured the House for the GOP, as Politico explains here. And a new analysis out today found that the 2021 gerrymandering diminished the number of majority-minority districts overall versus the prior decade, even as much of America’s population growth over the decade took place in these very communities.

Why is the other pending Supreme Court decision such a big deal? Because it would lock this all into place going forward.

Here’s the background:

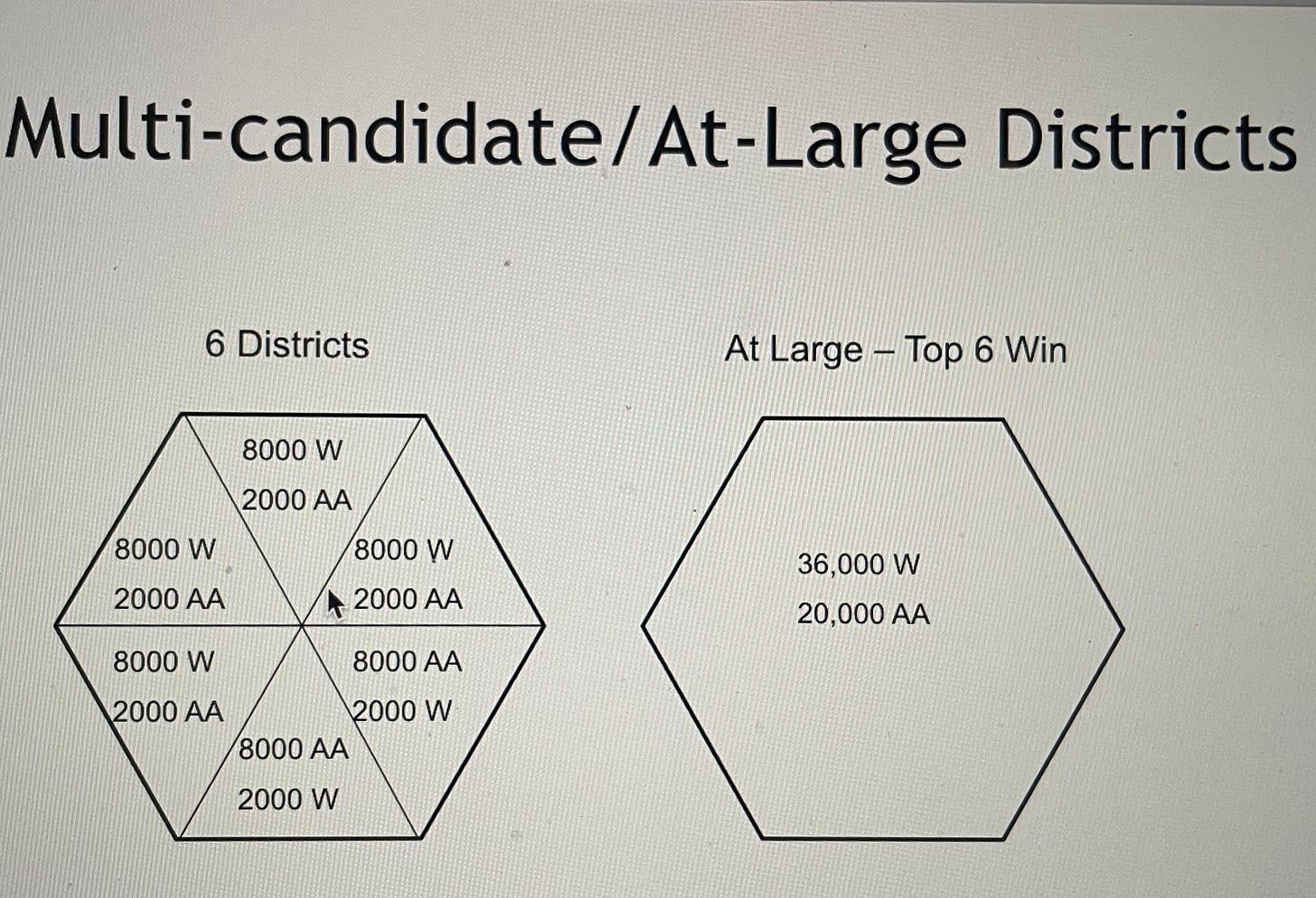

Several decades ago, once black voters registered in far bigger numbers, a key tool that continued to lock those voters out of legislative elections was a device called the multi-member district.

As opposed to single member districts, used in rural areas, these large multi-member districts were often used in allocating representation for urban and diverse areas. A much larger area and population would be combined into a single district, represented by multiple legislators (eg. one district the size of, say, six single-member districts would elect six representatives).

At-large elections within these multi-member districts would determine which candidates went to the statehouse, and in the process, would largely eliminate the more diverse representation that would have resulted if all the representatives from that urban area had instead come from single-member districts.

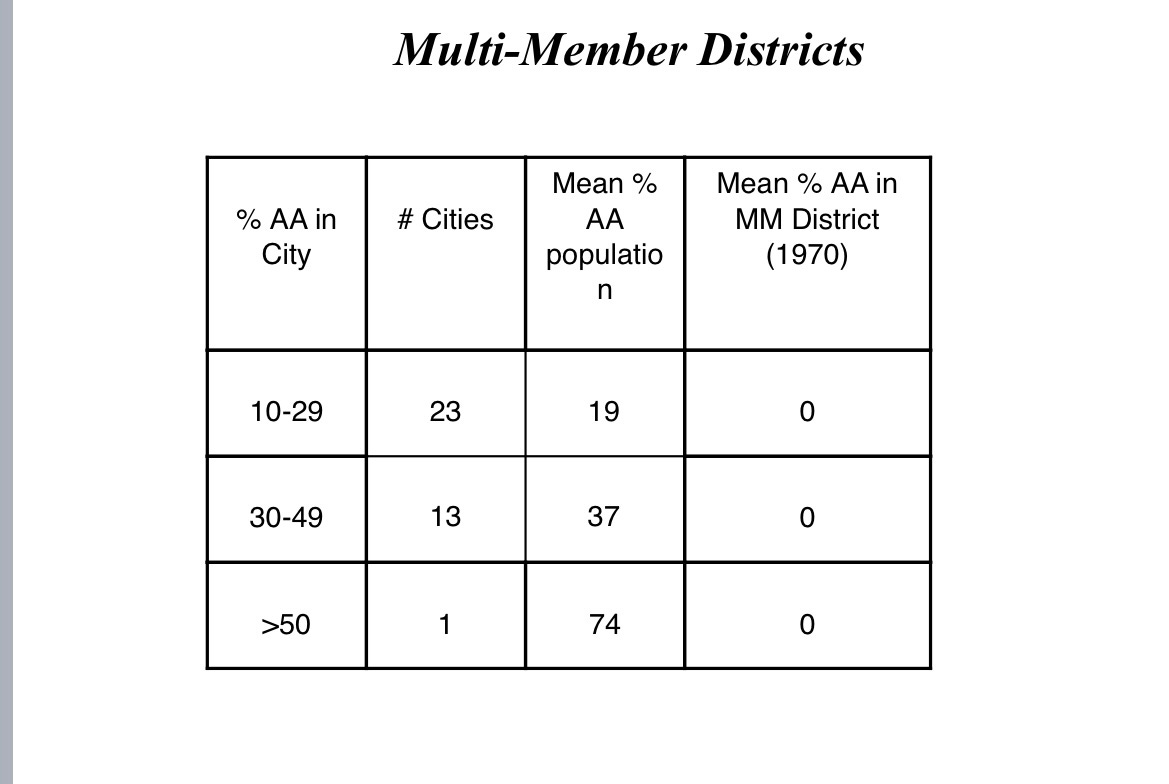

The graphic below shows how brutally effective these multi-member districts were in locking this new black electorate out:

Look closely. Even in urban areas with large Black populations, Black representation didn’t exist in city after city.

Enter the Voting Right Act.

Specifically, Section 2, which established that “[n]o voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice or procedure, shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizens of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

In a landmark 1973 case, the Supreme Court held that this language forbade multi-member districts if they were “not equally open to participation by” a distinct minority group.

After a later Court ruling watered down that ruling by requiring proof of intentional discrimination, a bipartisan Congress stepped in, amending the Voting Rights Act to clarify that Section 2 did not require discriminatory intent—only discriminatory RESULTS: “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State in a manner which results in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

Then, in a second landmark case, the Court held that this new Section 2 required that minority voters were entitled to an equal opportunity “to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice,” establishing a rigorous test to determine if a multi-member district deprived a minority community of that representation.

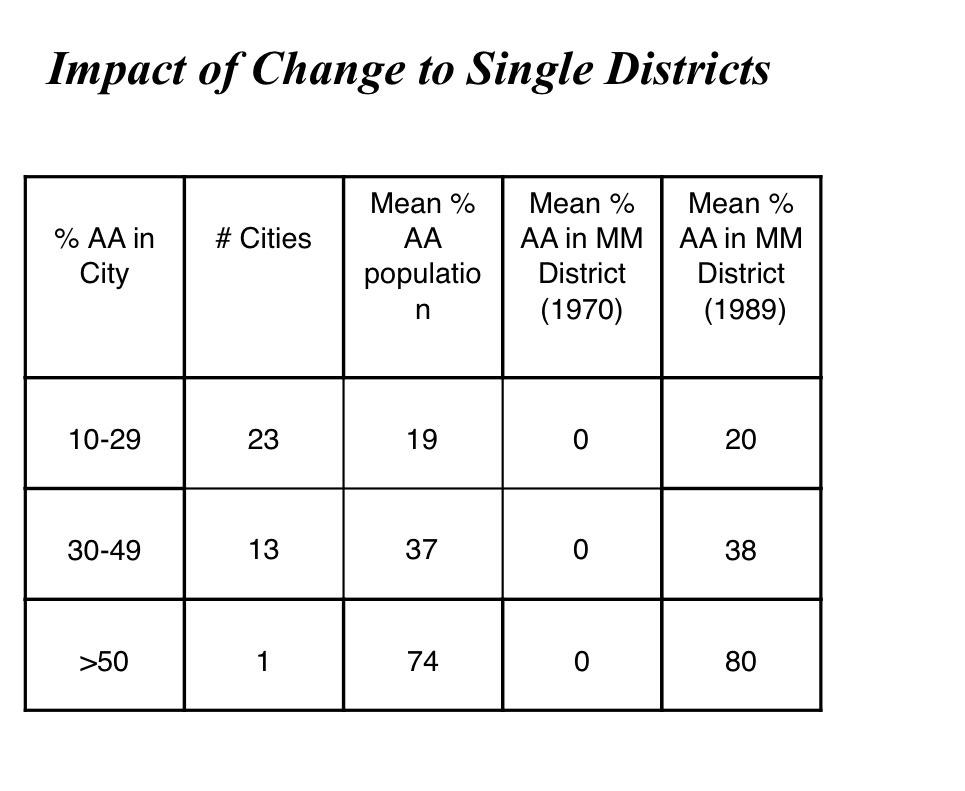

I know—this all sounds very legalistic. But the net effect of this approach was that it wiped out multi-member districts. And to see what that did, look at the updated graphic:

A stunning change. A representation revolution, really. And an example of just what a powerful tool the VRA became.

Importantly, the Court would soon go one step further, applying Section 2 and its new test not just to multi-member district cases, but all districts. And this meant the rule applied to challenges of gerrymandering processes that negatively impacted majority-minority communities.

Bottom line: anytime a distinct majority-minority community was split in a way that deprived it of representation, such a gerrymander was possibly subject to a Section 2 suit. And could be struck down under the Court’s test.

And THAT too became bedrock VRA law. A key protection (really, the only protection) against gerrymandering. And against the type of discrimination that would otherwise deprive majority-minority communities of representation at the state and federal level.

This has been the approach for decades.

Until now:

In 2021, numerous states engaged in the very splitting of majority-minority communities into different districts that this long-time approach outlawed. Ron DeSantis eliminated several majority-minority Florida districts at the last moment. In Tennessee, the GOP legislature split Nashville three ways. And so on.

In three cases—Louisiana, Georgia and Alabama—federal district courts (including Trump appointees) applied the Court’s clear precedent to find that the new maps violated Section 2 of the VRA. The courts in each case ordered new maps for 2022, adding the required majority-minority districts in each state. (Other states still have cases pending).

But then the US Supreme Court stepped in. In all three cases, the Court froze the ruling below, allowing the maps that had been struck down to be used in this year’s election. That’s right, the new House majority includes districts that lower courts held were in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

At the same time, the Court also took up Alabama’s appeal—the case is called Merrill v. Milligan—which was argued the first week of October. And here is where the case gets so dangerous.

Without getting into all of Alabama’s arguments about why its original map should be upheld (its prime argument is that the districting process must be “race neutral,” when the whole purpose of Section 2 is to combat the reality of racial discrimination, requiring that race be taken into account to some degree to protect majority-minority communities), the bottom line is that an Alabama victory would gut the long-time Section 2 approach that revolutionized representation in this country. And in the oral arguments of the case, conservative Justices sounded amenable to various aspects of Alabama’s argument.

Going forward, community after community would be subject to the same type of gerrymandering seen in 2021 with no recourse via the VRA. The result will be less representation of majority-minority communities across the country, which also stacks the deck more in favor of the GOP in statehouses and Congress.

What to do?

The best protection from all this lays with Congress. As they did after prior Court rulings, Congress can and must give teeth to the Voting Rights Act. This can not be treated as a back-burner issue ever again. To the contrary, this is ALL a direct attack on Congress and its duty to protect democracy and voting rights. They should be fighting back with a vengeance.

But the lesson for the rest of us is not to get complacent despite the election results a few weeks back.

This case is a perfect example of what a perilous moment it is for our democracy, and not just because of the likes of Donald Trump and Kari Lake. There’s a continuous institutional and legal attack taking place right now. Too few see it, or the deep damage it is doing. In this case, gerrymandered statehouses and the US Supreme Court have their sights set on dismantling another key pillar of the Voting Rights Act.

So whether it’s ensuring that we re-elect Senator Warnock in Georgia (which will help the Senate push back against a conservative judiciary), or shedding far more light on what each of our statehouses is doing, we all must keep fighting back.

As a lifetime voter and victim of party line primary voting that assists in the gerrymandering process. Party bosses manipulating candidate ballot placement and influencing funding and support. How long until both the parties are forced to participate in RCV ‘ranked choice voting’ to provide voters a break from the party parlor games? Elections can only bend so far.

Read this while “on hold” making calls for Warnock. You’ve inspired me to add more calling time!