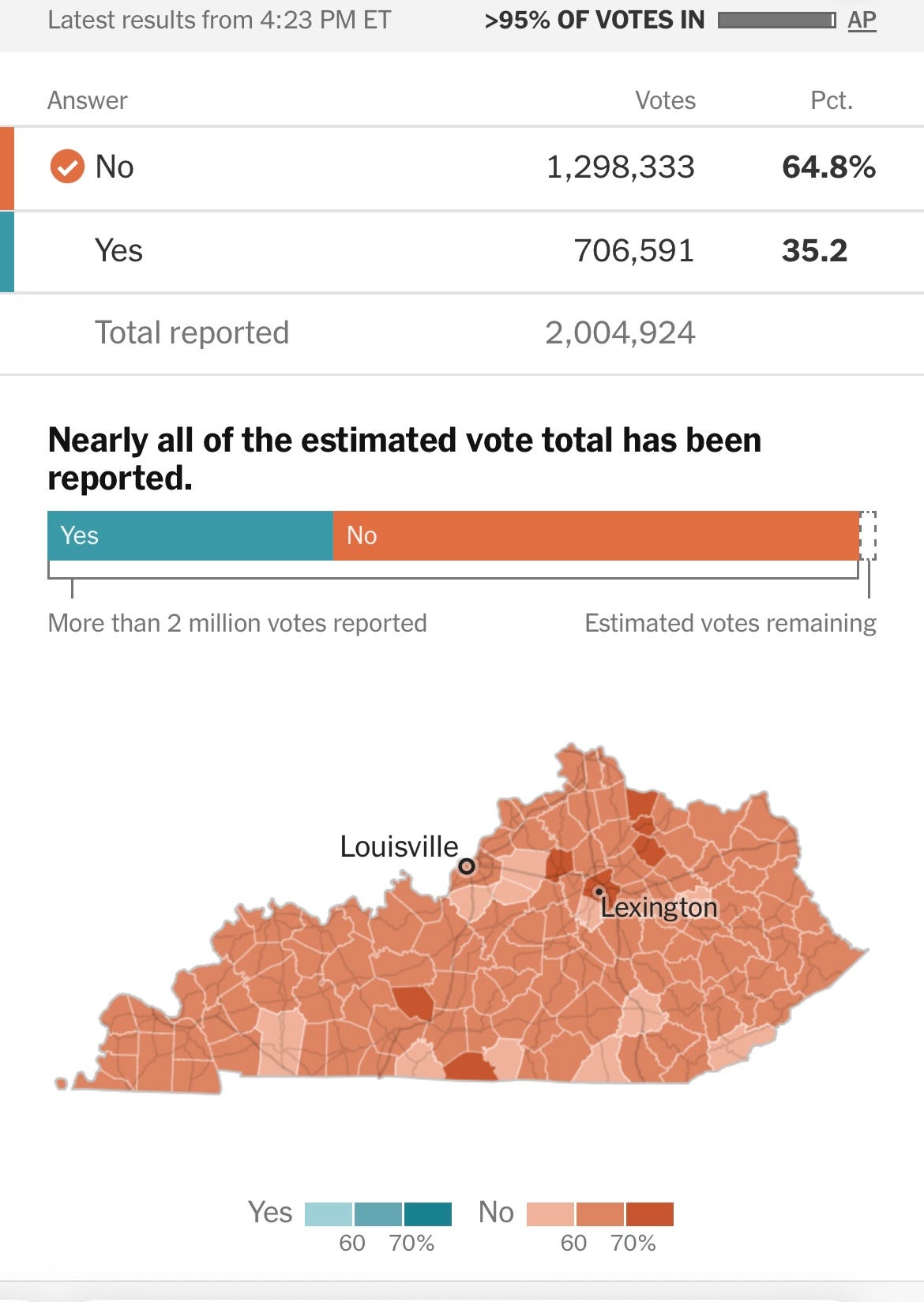

As I reviewed the data of the universal voucher referendum in Kentucky two weeks ago, several things stuck out.

The Amendment to add private school vouchers was absolutely routed: 65-35. (In a state Trump won by about the same amount: 65-34).

It lost in all 120 counties. And by 60-40 or worse in all but 9 of those counties.

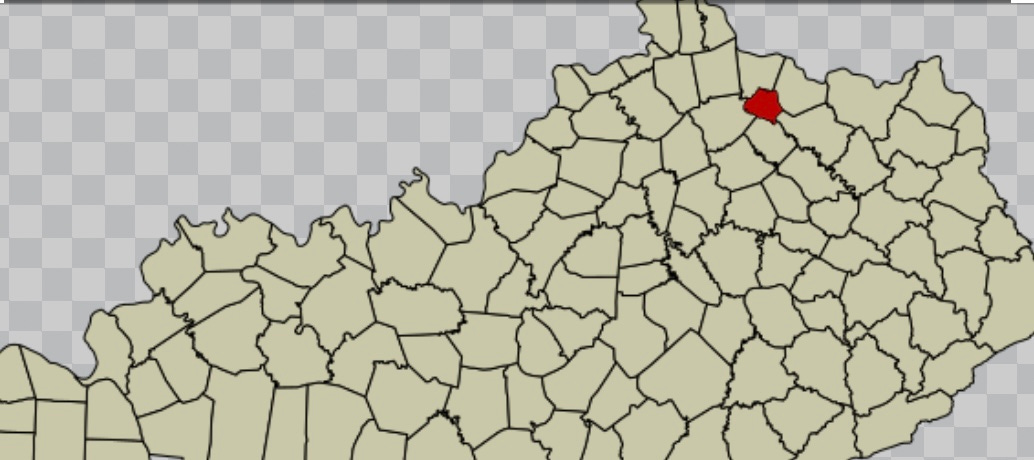

And—it did the worst in Kentucky’s smallest county: Robertson County. Population, 2,033 (as of 2023). It lost there 74-26!

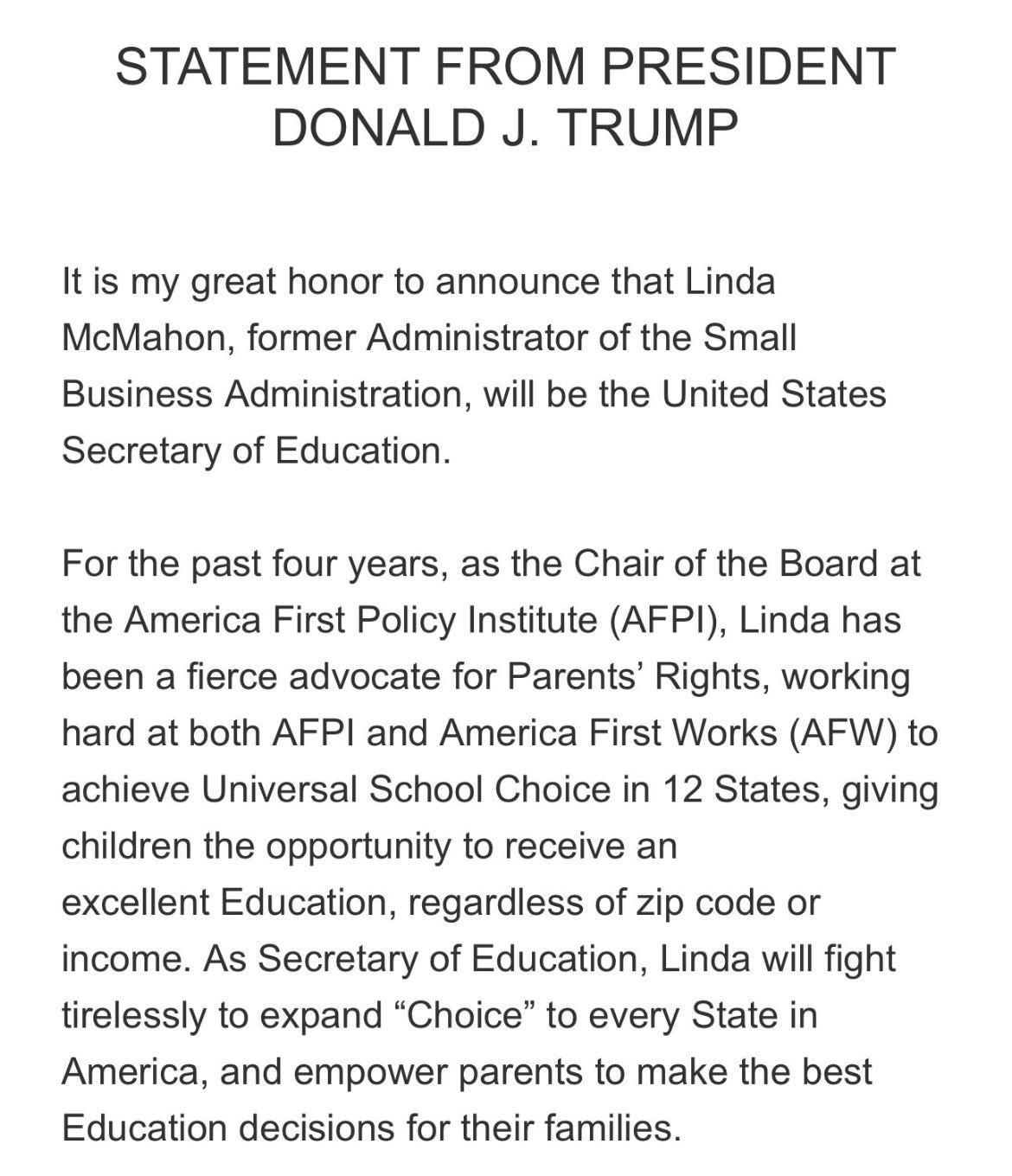

As context, Robertson County also voted 80-20 for Donald Trump. And yes, a key plank of Trump’s platform is to extend states’ failed universal voucher experiment to the federal level, which means vouchers could soon show up in all 50 states (by taking federal dollars that support public schools and converting them into vouchers). Trump made that clear again last night as he nominated his Secretary of Education:

So despite the strong support for Trump himself, Robertson County’s voters thoroughly rejected one of his core priorities.

Road Trip!

It turns out, Robertson County is about 65 hilly miles away from Cincinnati. The result there interested me so much, I decided to take a road trip:

So Monday, I set off for Robertson County and spent a few hours asking folks: why did your tiny, red county in rural Kentucky lead the entire state in opposing universal vouchers?

And the answers from the conversations (all pleasant) could not have been more clear.

Background:

Here are some basic datapoints on Robertson County:

As I said, its population is 2,033.

The county seat is Mt. Olivet, population 347 (in 2020). Here’s Mt. Olivet City Hall:

96.2% of the county’s citizens are white.

While 84.2% of county residents have a high school degree, 12.2% have a bachelor’s degree.

Per capita income is just over $24,000. 19.3% of county residents live in poverty (the state poverty level is 16.3%). Robertson’s is among the highest poverty rates in the Northern Kentucky region, but well below some of the poverty rates in eastern Kentucky (where Wolfe County leads the state with 34.6% living in poverty.) 26.9% of Robertson County’s children live in poverty.

To get a quick flavor of what the smallest county of Kentucky looks like—and how that poverty rate appears on its streets—here are some photos of the heart (the main intersection) of Mt. Olivet:

Why the People of Robertson County Crushed Issue 2

In my short visit, I stopped by a gas station, City Hall (see above), the County courthouse, the public library, and a grocery store, and approached various people to ask them about Issue 2.

I do not hold this out as a scientific survey, but the conversations sure told a story:

Awareness

As expected, people were at first gun-shy to talk to an out-of-town stranger asking about any political topic. But after that initial hesitance, my first impression was how well informed those I asked were about Issue 2 (a “yes” vote would’ve amended the Constitution to allow the state to fund students attending private schools).

One woman asked me right away: “Oh, you mean the ‘No on 2’ campaign?” (If you were opposed to Issue 2, that was surely a good sign right there).

Ownership

Of course, I didn't want to directly ask people how they voted (I got too close to doing that once, and got understandable pushback). So I eased into a broader question: I asked people to explain why they thought Issue 2 had done so poorly in their county.

But most of those I talked to still pivoted to their own view: “Well, I’ll tell you why I voted against it…”.

This was a vote they were proud to have cast, and that they felt strongly about; they wanted me to understand why.

And here were some of the reasons they gave:

A Simple Mantra

The initial response from everyone came in the form of a simple principle: they opposed public tax dollars being used to pay for private schools. This was said in different ways, but I heard the same theme from each person, articulated right away:

“I don’t think we should have pay to send kids to private school.”

“[I voted no because] money was going to go to private schools.”

“If I wanted to send my kid to private school, I would pay for that.”

That basic principle alone explained the outcome. (And it’s almost exactly what was said in the television ads.) I could’ve stopped right there. But I wanted to dig deeper:

Digging Deeper

Beyond the simple logic of it, most I talked to were willing to share why they didn't want to have their public tax dollars going to private schools:

Inaccessibility: first, the county has no private schools; and the closest would be at least a 30-45 minute drive away. This is true in states across the country, by the way. That’s right—the entire, national voucher push is forcing through a concept that the vast majority of communities simply couldn’t participate in if they wanted to.

Affordability/elite: the dollars would be sent to private schools “that people like me could never afford…..I shouldn’t have to pay to send kids to private school….Those people who are privileged get to go there.”

Exclusive: “what happens if the [private schools] won’t take [certain kids]?”

The Top Reason: Robertson County School

So it’s safe to say these voters were not interested in their dollars going to private schools.

But far more dominant in the conversations was where the dollars were going to come from—not just from them as taxpayers, but from their public school. That connection back to Robertson County School—and the risk Issue 2 posed to their public school—was key:

“Private schools don’t need the money from the county schools.”

“It would take away dollars from public schools.”

“Funds for our schools would’ve been taken away.”

Several people mentioned that this concern was heightened due to years of talk that the county might lose its school outright, and that services have already been reduced over the years:

“We barely have enough public funds for our kids programs.”

“They thought for years that they were going to close this school.”

“[There’s already] worry that the school might be shut down.”

“The school has been threatened for many years.”

We soon ventured into the reason why these residents were so eager to maintain Robertson County School. And it went way beyond just the classroom education provided therein.

It became clear, quickly, that the school serves as the center of the Robertson County community. A place of true personal connection.

In just a few minutes with each person, here’s what I learned:

The school’s principal stands outside “and waves every morning when you drop your kids off. Snow. Rain. Doesn’t matter what it’s doing, she’s there”

“We love our teachers….Everyone knows the teachers….They work the ballgames…” It was clear they weren’t just talking about these teachers as a group—but as individuals they personally knew

I was told of teachers at the school filling in the gap when kids/families in poverty (60% of the school’s students are economically disadvantaged) could not afford to buy holiday gifts as part of gift exchanges: “Teachers will buy the gift for the gift exchange. That’s what kind of a school it is.”

The school is a hub of other community activity: “everybody’s involved.” One woman summed it up in four words: “One school, one town.” A few examples:

the school hosted a Veteran’s Day program just the other day for the whole community

there’s a regular “Donuts with Dad” gathering, and a “Muffins with Mom” one as well

One woman I spoke to pointed to her earrings, which I hadn't noticed until she did — they displayed the school’s logo with the words “Cheer Mom” on them. Her daughter is a cheerleader, she beamed.

I met a retiree of the school, who said fellow retirees meet on a regular basis at the county library

Those I talked to did not think it was a coincidence that Kentucky’s smallest county was also the one that rejected the referendum the most decisively. A few offered that the county’s small size would be a major reason for the decisive “No” vote:

“We’re a very small town. We don’t even have a stop light, just a stop sign.”

“Most everybody knows everybody.” (I witnessed this as the woman who said this greeted everyone who walked past us by first name).

“It’s a small school; most people like that” (the entire K-12 is in one building, with a school population in the mid-400s.

It was clear that people knew the teachers, retirees, fellow graduates, and others.

It was also clear that when those involved in the school raised concerns about Issue 2—which they apparently did on social media (Facebook)—people listened. Remember— “we love our teachers”. We “know” them.

The School

So after hearing all this feedback, I went to the school itself. And in contrast to the run-down buildings in Mt. Olivet, here it stood—(along with the county library) the most impressive and modern building that I observed:

Remember the woman who said those four words to me, “One Town, One School”? Here’s what appears on the outside of one of the school’s windows:

Here’s some more school pride for you:

Here is an Agricultural and Research Farm on one side of the school’s campus:

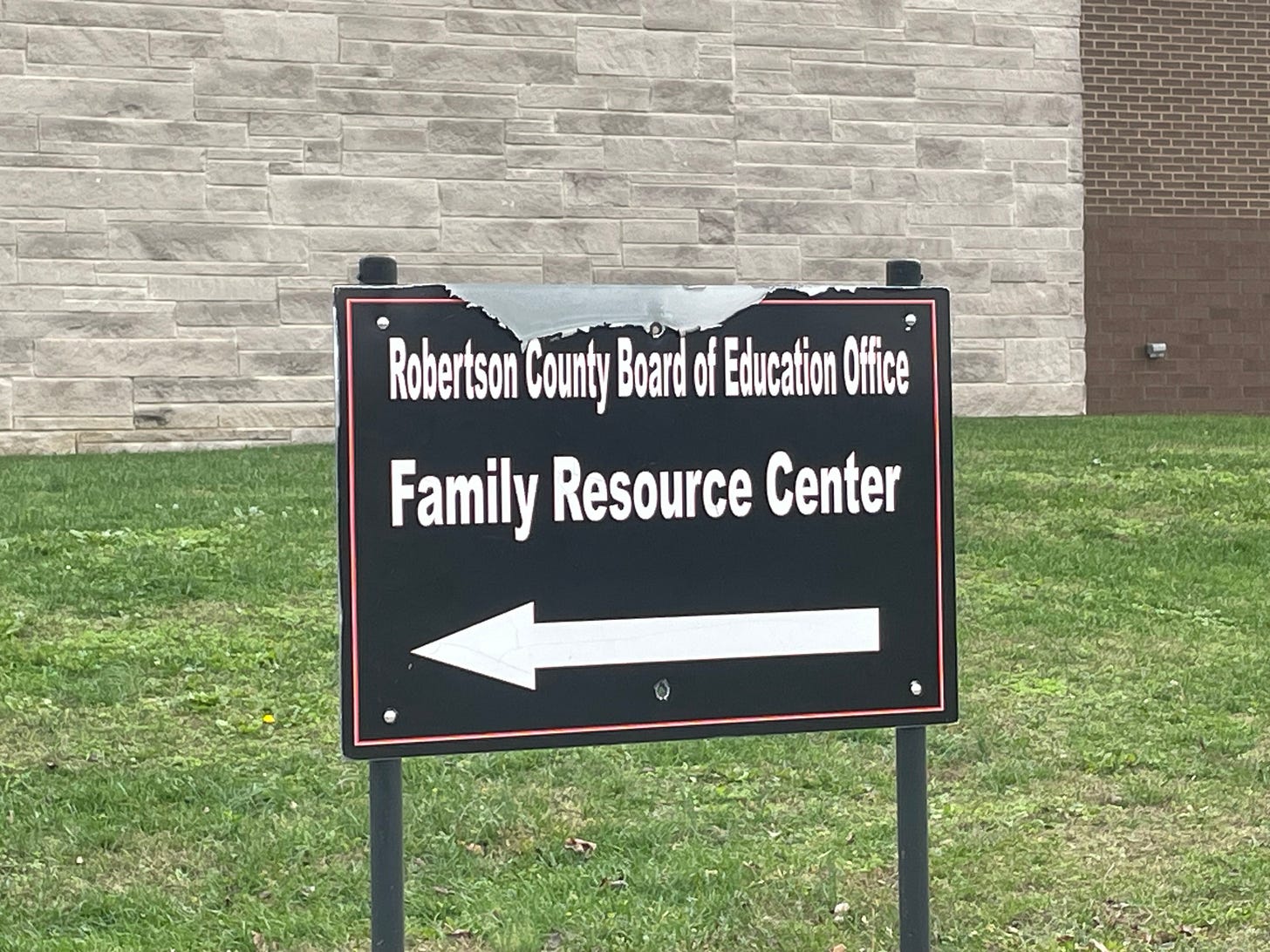

Remember how everyone said the school was the center of the community? About teachers helping kids in need? Here is the way to the Family Resource Center, which among other things, provides daily and weekend food assistance for families in need:

I didn't want to bother people in the school, but after hearing about those wonderful teachers, and the principal waving every morning, I sure wanted to meet them. Maybe next time.

Finally, on the way back into Mt. Olivet from the school, I came across this yard:

I knocked on the door in hopes of talking to this resident, but alas, nobody was home (except a few dogs, a cat and a nice souvenir for the bottom of my shoe). But the two “Vote No on 2” signs, with a large Trump flag in between, said a lot.

Summary

Take all this in. So much to learn from it:

1) On the attacks on public schools:

“One town, one school.”

How clear is that?!

Robertson County School is the prized centerpiece of this small community. Its beating heart. And the people of the county feel connected to it in deeply meaningful ways: they graduated there, their kids or grandkids go there, they work there—or worked there. They know and respect those who work there. They respect what the school and those who work there do within and beyond the classrooms.

As one woman told me, “it basically is” the community.

And as the one person I found who voted “yes on 1” told me (he was from a neighboring county, pumping gas), the school is the largest employer of the county.

Issue 2—taking dollars from Robertson County School and schools like it, to be sent to faraway and inaccessible private schools—became toxic here because it was viewed as an attack on the vital center of this small and tight-knit community.

“Whenever you threaten the school here, people here react,” one woman told me.

Indeed.

74-26 is quite the reaction!

My guess is that reaction can be replicated in virtually every community in America where public schools have established themselves in the way Robertson has (and most of them have).

“Whenever you threaten the school here, people here react.”

And even in his nomination statement last night, Trump is threatening Robertson County School. A key plank of the right-wing agenda across America threatens schools just like Robertson.

2) On organizing and communicating, more generally:

Community, community, community.

Beyond the topic of education and the county school, I was overwhelmed by the sense and power of community in driving the conversation in Robertson County. It was palpable in only minutes.

Relive what I wrote above:

the principal waves every morning, rain or shine

we love our teachers. we listen to our teachers. they voluntarily help the kids in need

we’re a small town. everybody knows everybody

we retirees meet every week

when people posted on Facebook that it would hurt our school, we were against it

Within the bonds and trust of this community, outside disinformation didn’t matter. Outside voices or money didn't matter. I guarantee you door knocks by strangers wouldn’t have mattered. If you knocked on the doors of those I talked to, and tried to convince them to vote “Yes,” it would have gone nowhere.

What mattered was that trusted and respected voices within the community were talking about the issue. They considered it a risk to their community. They expressed it person-to-person, and through regular community channels. And so most listened to that word-of-mouth wisdom and voted no.

And my guess is that happened long before the Issue 2 election hit Kentucky’s airwaves in the final weeks. (The pitch-perfect ads no doubt reinforced the message I heard).

NOW…

Do that on other issues. And elections.

Don’t airdrop in from above. Don’t only focus on targets cooked up on some computer somewhere. Know that outsiders and strangers, while of course helpful late in races, are not the ideal messengers.

Organize through community. Up from community. Through trusted local voices and folks who’ve earned credibility through years of service. Connections no computer will dissect, but that early and continued on-the-ground conversations can.

Break organizing “infrastructure” down to small enough networks and units (like the 2,000 people of Robertson County) such that you are within a space where “everybody knows everybody.” Small enough and with enough mutual trust that when some speak up, others listen. And have the conversations early—continually.

Those types of community conversations cancel out all the noise from the outside. And even the money.

Organize accordingly. Build infrastructure accordingly.

Start conversations. And do it soon.

For a lot of reasons.

But one to keep in mind at this moment—the Trump and Project 2025 agenda are about to undertake a direct assault on communities like Robertson County.

“Whenever you threaten the school here, people here react.”

Share this post