Steubenville, Manchester...and Democracy

Lack of Accountability and the Struggle of Small Towns

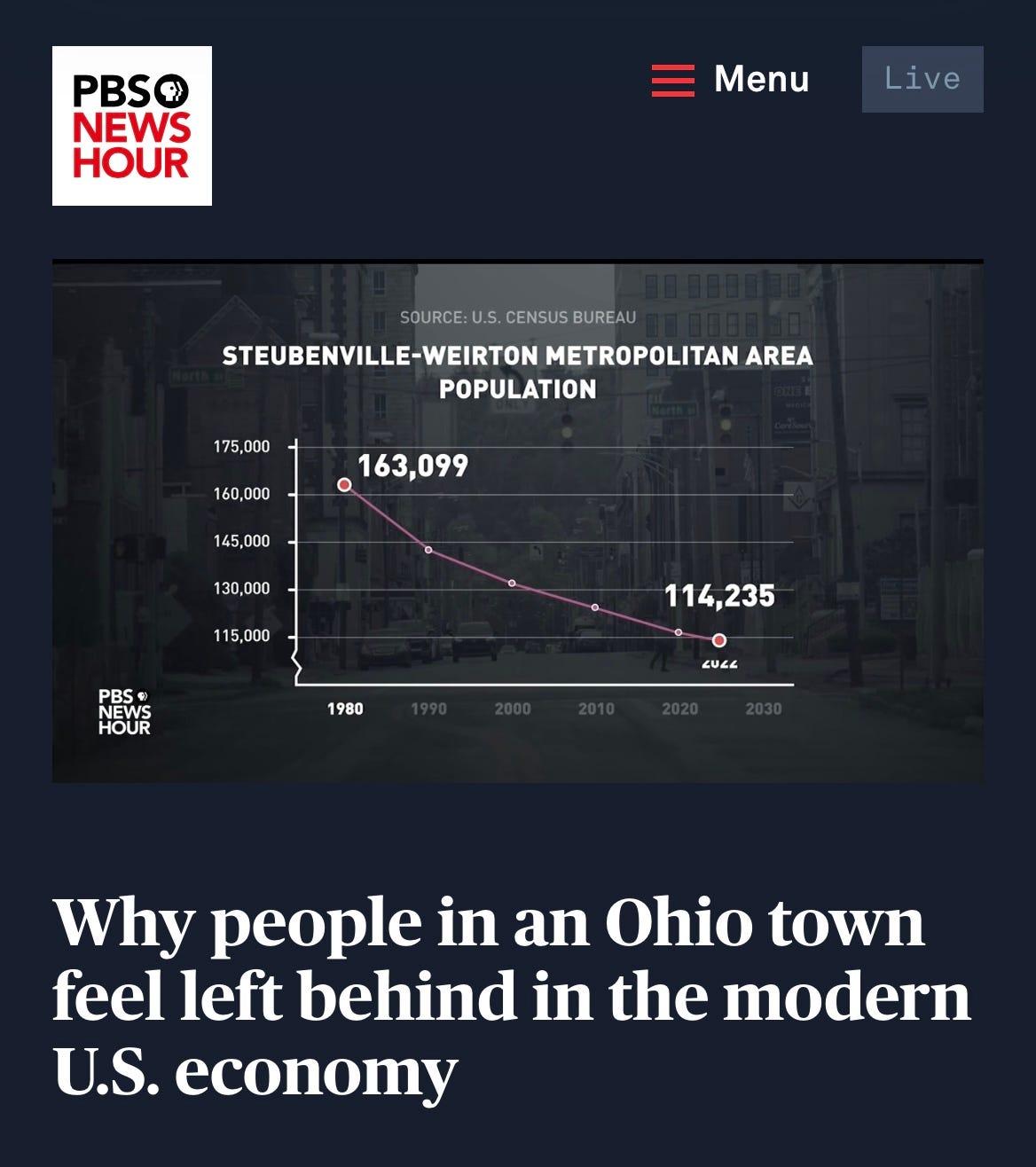

Last night, PBS and the iconic Judy Woodruff aired a story about the plight of Steubenville, Ohio. You should watch it. All of Ohio should.

You can watch it HERE:

It’s the story of Ohio that state leaders don’t want told. That while they veer far to the right and wage endless culture wars, communities across this state are struggling mightily. And that even amid a national recovery, many towns continue to decline by almost all economic and other indicators. (For life expectancy, for example, The Washington Post ran a story recently on just how poorly some Ohio communities are doing, focusing on another town, one due north of Steubenville—Ashtabula).

And the “policies” emerging from the state capital are not reversing this trend. To the contrary, in too many ways, those policies are actually contributing to the downward spiral.

There’s a lot more to say about these policies. I’ll discuss them in future newsletters and through future work.

But for now, the Steubenville story takes me back to another struggling river town, and the opening scene of a key chapter of my book, “Laboratories of Autocracy.” Because I believe that the underlying problem isn’t just so-called policies themselves. It’s the set of warped incentives that drive them.

And those incentives all emerge from deeply broken politics.

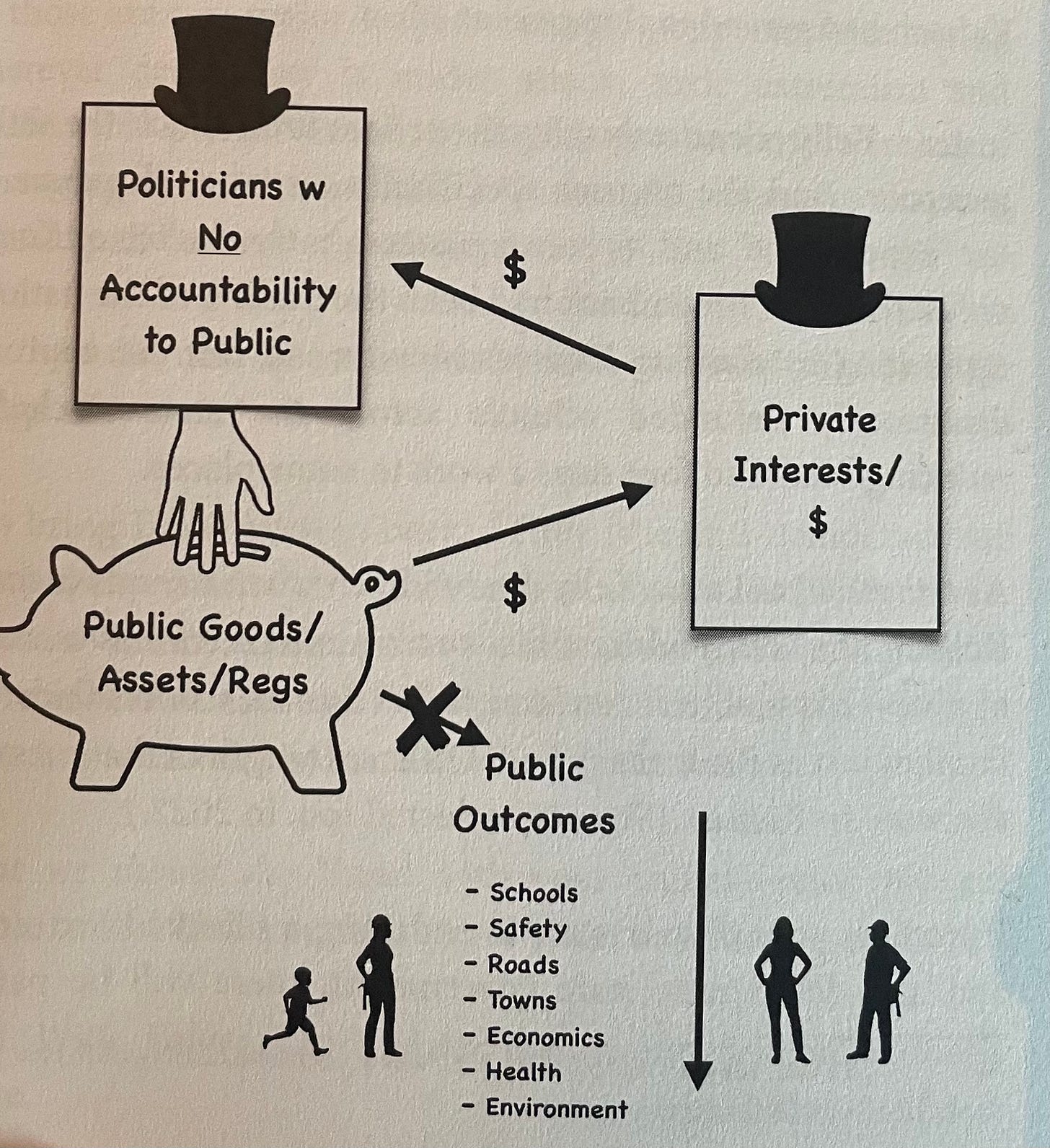

More fundamentally, it’s the lack of democracy in Ohio—which has bred years of lack of accountability for those shaping policy at the state level. That lack of accountability to the public writ large is what mis-shapes those policies from being about the public good in the first place. And it’s that same lack of accountability that keeps those policies in place, year after year, even as they fail to serve the state, its people or its communities. But the same people advancing the same failed policies return to the Statehouse, term after term, amid all that failure back home. Especially lately, they return to the statehouse only to double down on all those failed policies. Because their policies do benefit some people and interests in Ohio—just not communities like Steubenville.

So, despite all that failure, nothing ever changes. And none of them ever fear being replaced.

To tell this story in Laboratories, I highlight a town going through the same struggles as Steubenville—perhaps even worse. Here’s the excerpt—with photos added that aren’t in the book:

“Just Move:” A Terrible Incentive Package

Sixty miles east of Cincinnati, sitting right on the Ohio River, is a small town named Manchester. Locals will proudly tell you it’s the single cleanest point of the river.

The small town sits in the southwestern corner of Adams County, where my wife Alana grew up, so we spend a lot of time out there. As you wind along the hilly roads of the county, you often find yourself slowed behind an Amish horse and buggy. But you don’t mind the leisurely pace because you’re surrounded on both sides by a wondrous sea of corn and soybean fields, with an old farmhouse nestled in nearby.

When you arrive in Manchester itself, the idyllic scene ends abruptly. And that’s when my blood boils. Almost every storefront on its Main Street is shuttered. Stately old buildings . . . empty. Hardly a soul on the street. It looks like a ghost town—depressing as hell. And all only a block from the river, which offers the town so much potential.

Manchester has struggled for some time, hit especially hard by a flood a few decades back. And then in 2016, the largest employer in the area, and largest taxpayer—Dayton Power & Light—shut down. Jobs just evaporated and, with it, the town itself.

A few years ago, concerned citizens of Manchester approached their state senator on how to halt the decline. Mind you, this senator had voted routinely for tax cuts for those at the top, almost none of which ever “trickled down” to lift the people of Manchester. He’d voted to raid the precious local funds from Manchester to pay for those tax cuts. He’d voted to move money out of the strapped Manchester public schools.

Faced with the direct result of those and other statehouse policy failures, what did he tell the concerned citizens? Did he offer a new idea? Some kind of plan of action around infrastructure? Legislation to help struggling Main Streets like theirs?

No. No. And no.

What was his advice?

“You need to move.”

Just leave, he said.

When asked about the comment, he later confirmed it: “I did say, ‘Sometimes you have to do what’s best for your family.’” Yep. Just leave. It’s best for your family. (For the whole story, read here.)

Think about that.

After this politician and his colleagues absolutely failed this community, with no solutions in sight, its residents don’t get to say it’s time for him to leave. Instead, he tells them that they should go elsewhere.

And for the most part, that’s what happened. Manchester remains a ghost town, its population dropping below 2000 people for the first time in 90 years. And while term-limited, the senator’s doing just fine—he got himself a job with the Ohio Department of Transportation.

Needless to say, that conversation—that entire story—is not how representational politics is supposed to work. It’s actually the opposite of how it’s supposed to work. But the Manchester story is just one of many grotesque distortions to politics that arise when you have a decade without democracy.

A Decade with No Democracy: All the Wrong Incentives

A few years back, I had a heart-to-heart conversation with the leaders of the Ohio Manufacturing Association. When we arrived at the topic of the Ohio statehouse, I tried to put the problem in terms they’d understand.

If the businesses they ran operated with the same incentive structure that exists for statehouse politicians, they’d all go bankrupt quickly. Because the incentives arising from the corrupt and rigged legislature don’t in any way reward delivering outcomes that serve the broader public good.

As a legislator with eight short years to move up in the world, you’ll do far better by helping the big donor make a mint off his for-profit school than you will helping the public schools back home in your district, where they don’t know what you do anyway. More broadly, serving private interests earns you far greater rewards than the public interest. And as a politician in a rigged district, the biggest risk you face is being outflanked by an extremist in your next primary, so your incentive is to be as extreme as possible. Even if public outcomes plummet, so long as you are extreme and cater to those private interests, you and your colleagues are reelected, no sweat. And the one thing that will get you ousted from office? Working with the other party on anything. So never do that!

That’s it, I told them. That’s the game. And in any enterprise, such a dysfunctional set of incentives would guarantee failure— and worse—as it does for the state of Ohio.

Even more than I could capture in that meeting, a decade without actual democracy in Ohio’s legislature has taught searing lessons about what happens when politics lack any accountability. When democracy doesn’t really exist. And it’s shown just how out of whack and dysfunctional those incentives become, and how much damage they cause.

Here are the worst of them:

No Accountability for Public Outcomes

What happened in Manchester illustrates the first consequence of a decade with no democracy—a complete lack of accountability for even the most disastrous of public outcomes. In a system where elections don’t matter—where there is little awareness of what happens in the capital city and no electoral consequence for its failures—there is simply zero incentive to improve public outcomes.

Give them credit.

The citizens who tracked down that state senator took a step only a tiny fraction of citizens would think to take: request a meeting with their elected senator (who most couldn’t name), plead their case, and ask for answers. And still, he didn’t even pretend to have answers. He told them to leave. That’s a man with absolutely no concern about being held accountable for the failed outcome he and his colleagues are delivering for communities like Manchester.

And that’s one reason you see failure across the board, and towns in the sad shape of Manchester across Ohio. It’s not that a policy or two are wrong-headed. It’s that the culture and structure of Ohio politics creates no incentive to deliver broad-based, positive public outcomes in the first place. So that’s not the goal on issue after issue.

Take a step back.

Why should a state with the Cleveland Clinic and children’s hospitals of the highest quality be ranked so low in public health access? Or ranked one of the worst in the nation in infant mortality? One reason that comes to mind: Ohio government ranks 47th in the nation in the amount it spends in public health, per capita. There’s just zero incentive to do more. Or better.

Why should a state with the seventh largest economy experience high poverty in city after city? Two of the ten poorest cities in the nation? One reason: the state legislature has been pushing trickle-down policies for years, including raiding cities like Manchester, Cleveland and Cincinnati of local revenue (well over $1 billion over the course of the decade)201 in order to afford tax cuts for those at the top. There’s no incentive to do better by those communities—the average voter has no idea the state has taken those funds (which, by the way, defunds local police). You can even tell them to leave their community without worry about any political reprisal.

Why should a state with so many strong colleges and universities, with the fifth best public secondary schools in the nation as recently as 2010, now rank so low in higher education attainment, while still lead the nation in student debt? Could it be because state government underfunds those colleges, forcing more of the burden on families as tuition and debt? If no one knows, and there’s no accountability (they blame the college or local school board, not the statehouse), there’s simply no incentive to change it.

To be clear, I still have faith that many state legislators come to their statehouses to do good by their communities, or to make a difference on issues they care about. They still view the role as public service. And I’ve seen many work to do that every day of every term despite countless obstacles. But over time, and across hundreds of people that cycle through over the years, the institutional incentives drive both the goals and the results of the institution as a whole, and too many (including a majority) of its participants.

So with little to no incentive to improve public outcomes, Ohio is suffering the precise results you’d expect.

And just like in Manchester, across the state, people are leaving in droves. But the politicians and their broken politics stay right where they are, powerful as can be amid failure after failure.

A Powerful Incentive To Serve Private Interests

On the other hand, politicians in Columbus face a powerful incentive to satisfy the narrow, private interests reviewed in Chapter Three, and beyond (as we’ll see in Chapter Six).

They get elected to the statehouse for four terms. That’s eight years to garner something meaningful out of their service before finding their next step in life. The clock starts ticking right away.

Most will serve their eight years and be done. For most, the best prospects for that next step will come from that capital city as opposed to back home. From the private players who surround them. So, best to get along with them as well as you can.

Others may have aspirations beyond the initial elected post. One group tries to be lifers—jumping from the house, to the state senate, and back to the house. Some pull this off. For example, the senate leader orchestrating the 2021 districting process is the same person who, as a member of the house, rigged the maps in 2011.

Others aim higher, like Congress or statewide office.

Either way, playing the capital city game is the surest ticket to success in any of those directions. Running for Congressor statewide is a multi-million-dollar enterprise in a state like Ohio. Outside of a few big cities, the political money is largely concentrated in Columbus (or DC). To make that leap up— when you only have a few years to do it before your window of relevance closes—you’ve got to be in good with the powers that be. Especially, again, when the people back home have no idea what you actually do.

Just look at the trajectory of (Lieutenant Governor) Jon Husted from young house member, to Speaker, to statewide office. He succeeded by building relationships with David Brennan and William Lager and Bob Murray and First Energy, not by standing up to them. And he built those relationships by doing what they wanted, when they asked. Writing the law that allowed their for-profit operations to start lapping up public education dollars. Eliminating the nagging agency that was warning about their problems. Gerrymandering the state behind closed doors despite promising reform publicly. And so on. All upside, no downside, even when it all explodes in scandal and lost public funds.

So, the decline in Ohio doesn’t just result from the fact that there’s no incentive to deliver positive public outcomes. It’s worse. Much of that failure results directly from powerful incentives to satisfy the private interests urging policies that undermine the public interest. Policies that drain public assets.

The rapid decline in Ohio schools? If your politicians are willing to pull money away from more successful schools and throw that money to scams like Lager’s and educational disasters like White Hat, of course your school ratings are going to fall. If leaders are willing to eliminate the agency that’s trying to fix the problem, of course there’s no accountability.

An economy struggling to compete in the 21st century? If your politicians are willing to smother emerging industries— like solar and wind—in the crib because dying industries like Murray Energy tell them to, of course you’re going to fall behind.

Ohio’s decline is not a policy problem, because policy is not the goal anymore.

It’s a pay-to-play problem. These legislators are catering to certain private interests that dominate Columbus and other state capitals, and those interests too often have their eyes on public assets they can tap into for their own gain.

What the people actually want, and what would actually benefit the state, are, at best secondary; worse, wholly irrelevant; and worst of all, the exact opposite of what the private interests are demanding from government. And legislators learn quickly that serving those private goals, even at the cost of public outcomes, strengthens their grip on power.

So, in the end, the incentive to please these private interests directly correlates with failure in public outcomes.

But there are other incentives that are just as poisonous….

About as perfect of summation as one can read about why the economies and lives of the working class in red states are in the crapper. The thieving foxes in their own statehouses are killing them economically bit by bit and year after year, yet many of those same working class people gasping and grasping for help as they and their communities are drowning in ever increasing poverty blame Joe Biden instead of their own state representatives, state senators and governors who are robbing them blind of any kind of economic well-being.

So, instead of electing people at the state level who’ll actually enact policies that’ll help them take the journey up and out of poverty and despair, they look at freaking Trump to “save” them, when he’s multiple times worse than the members of their own statehouses in regards to not giving a shit about them, and will only exacerbate their problems with his worthless policies which are fueled by his own ginormous personal greed for wealth/power and his cold, dead, uncaring heart.

As always thank you David. Allowing these companies to ship the product production to southern states that are right to work, which keeps wages low and or taking the production lines out of the country has been one of the biggest contributors to our poverty rates. Lose of jobs also has an effect on drug use. IMO. I’m just hoping that the democrats have some great candidates lined up to run for the state next year. We have to get Sherrod Brown re-elected to keep the majority in the Senate. We can’t have Frank LaRose elected to Congress. Or Jon Husted to governor.