Day 11 — December 11, 2024

After J. Edgar Hoover towered over the FBI and Washington for 48 years, Congress passed a law to create a single, ten-year term for all future FBI directors.

A Committee report at the time made clear that the goal was to strike a balance: the ten year-term ensured that no director would accumulate too much power or overstay his or her welcome.

But that set term—longer than the tenure of any single president and separate from the four-year presidential cycle—ensured that an FBI director was not simply the subject or agent of a single president: “[t]he position is not an ordinary Cabinet appointment which is usually considered a politically oriented member of the President’s ‘team.’“ If the director served as an ordinary political appointee, there is too much risk of “infringing individual rights and serving partisan or personal ambitions.””

A simple reform—but a meaningful one.

Ever since this safeguard was enacted, standard procedure has been that the sitting FBI director carries forth through presidential terms until the end of the 10-year term. Only then does the president nominate a new director. Generally, this has accomplished the goal of assuring independence on the part of the Director and the FBI. And when a president fired an FBI director amid the 10-year term, as Trump did James Comey, it was viewed (to put it mildly) as a significant break from that established norm.

Current FBI director Christopher Wray was appointed in Trump’s first term (following the termination of Comey). He is in year seven of his ten-year term.

Last week, despite the fact that Wray still has three years remaining in his term, Trump announced that a far-right ally and conspiracy theorist named Kash Patel would serve as his new FBI director. Patel has infamously compiled a list of so-called Trump political enemies against whom he has promised to seek retribution. It is clear that both Trump and he intend for him to serve Trump’s personal and political interests.

One obstacle to their plan was the 10-year term. (Trump did not cite a reason for why Wray should be replaced.)

On December 11, Wray announced he will resign after the new year. By doing so, he has acceded to Trump’s violation of the norm.

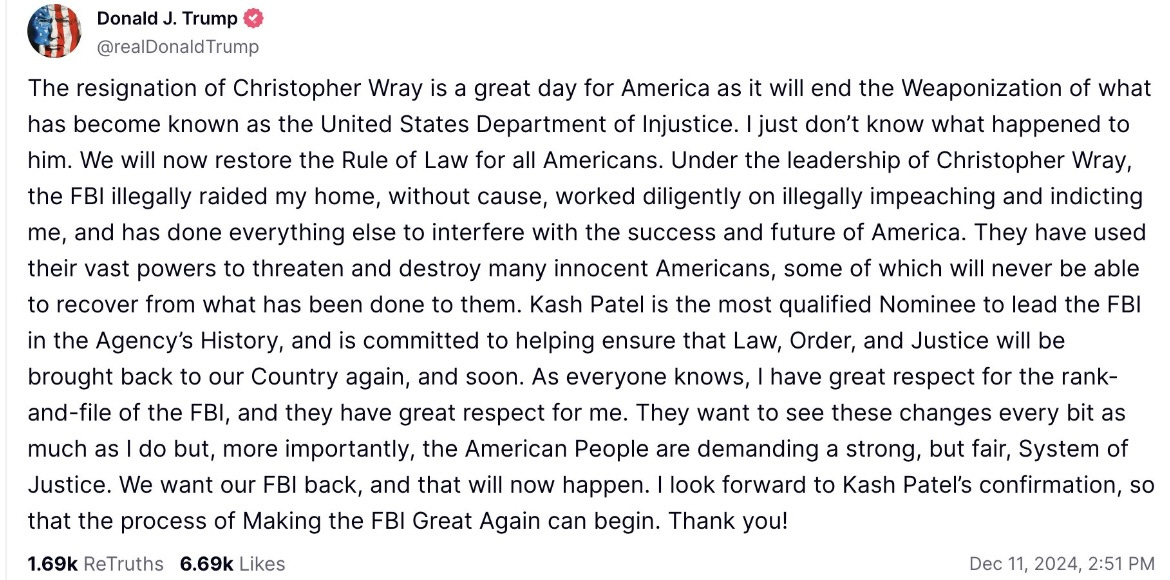

As always, Trump’s response to such weakness is to pounce. In a post following Wray’s announcement, Trump attacked the Department of Justice, the FBI and Wray himself (making false allegations of its investigations into his own conduct), and falsely touted the credentials of Patel. “We want our FBI back,” Trump wrote, “and that will now happen.”

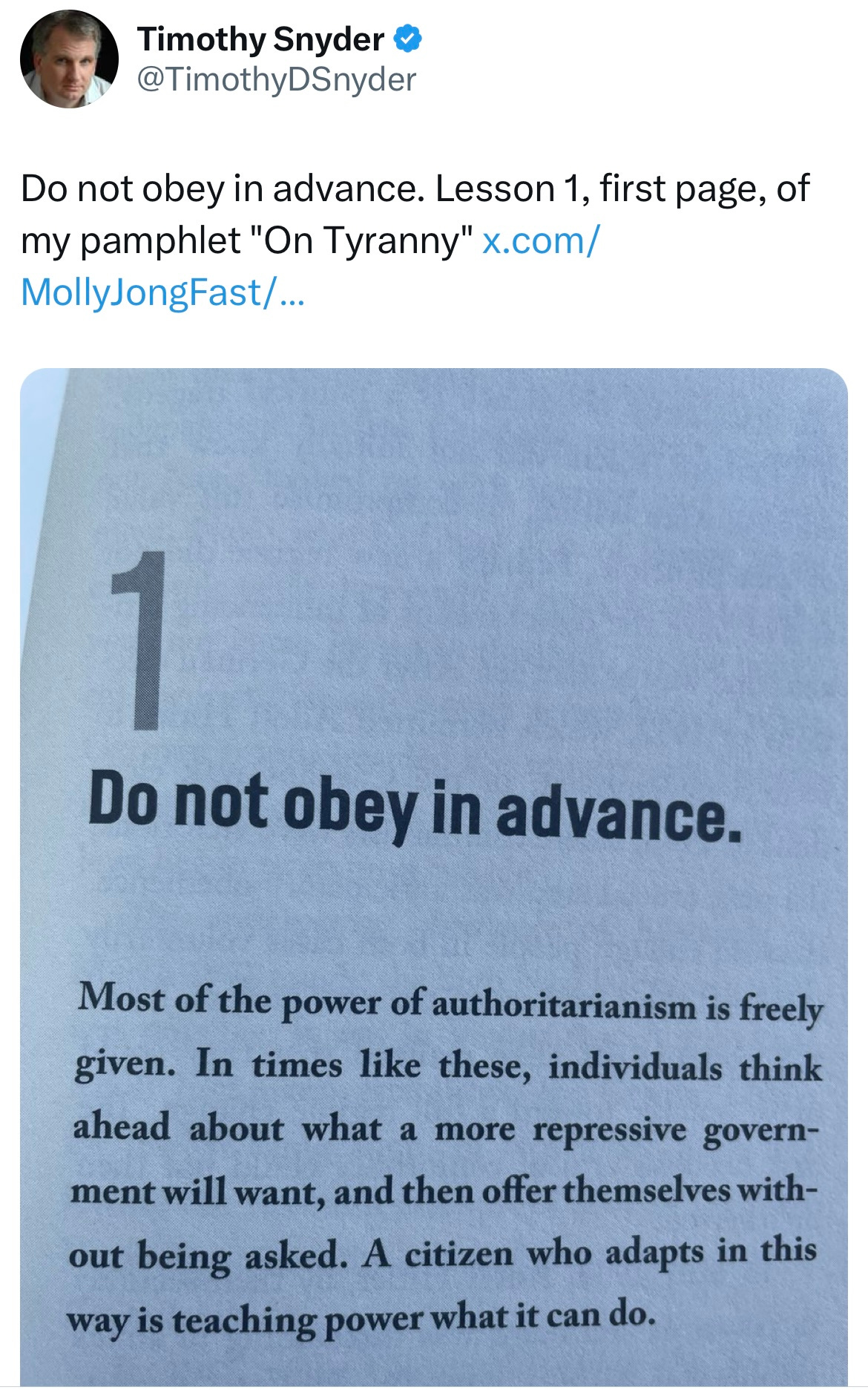

Historian Tim Snyder famously instructs: “Do Not Obey in Advance.”

Wray resigning—passively shattering a safeguard that has been in place most of our lifetimes and giving Trump the opportunity to rewrite history—is a case study on the deep and instant damage of violating Snyder’s principle, especially by those in positions of power.

Things may not be so simple. Read David French in today’s NYTs:

”By stepping down now, as the conservative writer Erick Erickson observed, Wray has created a “legal obstacle to Trump trying to bypass the Senate confirmation process.”

Here’s why. According to the Vacancies Reform Act, if a vacancy occurs in a Senate-confirmed position, the president can temporarily replace that appointee (such as the F.B.I. director) only with a person who has already received Senate confirmation or with a person who’s served in a senior capacity in the agency (at the GS-15 pay scale) for at least 90 days in the year before the resignation.

Kash Patel, Donald Trump’s chosen successor at the F.B.I., meets neither of these criteria. He’s not in a Senate-confirmed position, and he’s not been a senior federal employee in the Department of Justice in the last year. That means he can’t walk into the job on Day 1. Trump will have to select someone else to lead the F.B.I. immediately, or the position will default to the “first assistant to the office.”

The trouble with Trump and everyone who deals with Trump is that NO means nothing to him.